Intro

This tutorial will introduce the process of reverse engineering a game. We’ll use the Nintendo DS game Pokémon Mystery Dungeon: Explorers of Sky for demonstration purposes, although most concepts discussed here can be applied to other games.

What is this tutorial about?

This tutorial will walk you through the following:

- Setting up a reverse engineering environment.

- A basic introduction to assembly code.

- Using the reverse engineering tool Ghidra to analyze assembly code.

- Exploring debugging features of the DeSmuME emulator to inspect a game’s memory and debug the game while it is running.

- Reverse engineering strategies for finding game mechanics and data.

This tutorial discusses several reverse engineering aspects unique to DS games. If you are looking for a more general reverse engineering tutorial, I recommend following the GBA version of this tutorial.

What skills do I need to follow this tutorial?

- Programming knowledge (ideally C or C++), along with the following programming concepts:

- Pointers

- Structs

- Bitwise operations

- Hexadecimal (base 16) numbers

- Basic fluency with using an emulator to play games.

- Interest in reverse engineering games!

Table of contents

- Intro

- Table of contents

- What is reverse engineering?

- Setting up a reverse engineering environment

- Assembly primer

- Using Ghidra

- Debugging with DeSmuME

- Reverse engineering strategies

- Conclusion

What is reverse engineering?

In the context of programming, reverse engineering is the process of figuring out how a program works without access to the program’s original implementation, i.e., source code, documentation, etc. Most games do not release their source code publicly, but it’s possible to learn and reconstruct many details about a game by analyzing binary data in the game files.

There are several reasons to reverse engineer a game:

Knowledge

Games hide many details about their mechanics and implementation, and empirical experimentation in-game only gets you so far. Enter reverse engineering, where you can analyze the game’s code and find out precisely how a game works. With enough game knowledge, people can apply this knowledge to build useful tools like a damage calculator for Pokémon battles, or even an entire battle simulator.

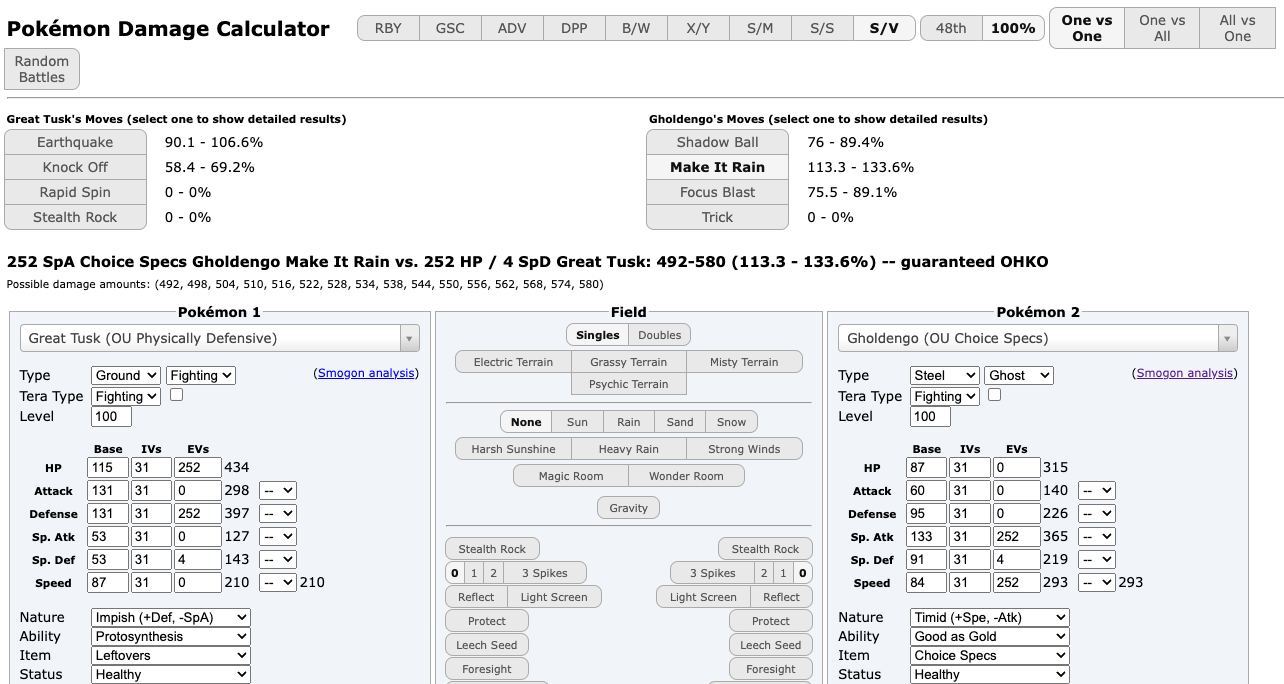

Behind this damage calculator is a complicated formula, discovered through reverse engineering.

Modding/Hacking

How do you build custom levels in games without a built-in level editor, create a cheat code that lets you fly infinitely, or give your character a silly custom weapon? Most of the time, people reverse engineered the game and figured out how to modify the game code to add these features. Cheat codes, namely those for devices such as the GameShark and Action Replay, also require reverse engineering to create; a cheat code is simply a set of encrypted instructions for the cheat device to set specific values in memory or inject small amounts of code into the game.

Exploiting glitches

There is a category of glitches called arbitrary code execution (ACE) that allows a player to inject code into a game to perform basically anything the hardware supports. This includes giving yourself infinite items, instantly warping to the end credits, or turning a SNES into a Skype video chat. ACE requires detailed knowledge of the game’s code to exploit to its fullest, and reverse engineering plays a large part in crafting these exploits.

Just a normal SNES running The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. With massive glitches and arbitrary code execution.

Datamining future content

In games with recurring content updates, developers sometimes add new assets into a game prior to their official release. Early-release demos may also hide parts of the full game. Dataminers can reverse engineer games to extract these assets and learn about new content before it is officially revealed.

Setting up a reverse engineering environment

You’ll need the following applications for this tutorial:

- Ghidra - a reverse engineering tool used for static code analysis.

- DeSmuME - a DS emulator with debugging and memory viewing capabilities.

- A ROM of Pokémon Mystery Dungeon: Explorers of Sky - the game we’ll reverse engineer. Make sure to use the USA/NTSC version of the game; other versions like the EU/PAL version have differences that change the locations of data and functions.

This tutorial uses DeSmuME as the DS emulator of choice, though it is worth mentioning another DS emulator commonly used for debugging, No$GBA. No$GBA has more advanced debugging features than DeSmuME, but is less stable and less user-friendly.

Only the Windows version of DeSmuME has the proper debugging capabilities for reverse engineering. Unfortunately for macOS/Linux users, the only option for debugging DS games on these OSes is DeSmuME’s partially functioning gdb stub, which doesn’t work very well even if you are familiar with gdb. Ghidra is compatible with all OSes, so you can opt for a setup with Ghidra on macOS/Linux and DeSmuME on Windows if you prefer. Alternatively, you can follow the GBA version of this tutorial, as there are GBA emulators for macOS/Linux that support debugging.

The following Ghidra setup is adapted from the excellent setup guide written by UsernameFodder as part of the pmdsky-debug project.

Unpacking the ROM

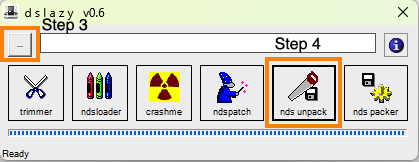

To start analyzing a DS ROM, you’ll need to unpack its contents to extract binary files containing the code for the game. To unpack a DS ROM, you can use DSLazy (Windows) or ndstool (macOS/Linux).

Using DSLazy

- Download DSLazy and extract the zip file.

- Run the DSLazy application (

dslazy.exe) to start the program.

The DSLazy interface - Click … in the top-left of the DSLazy window and select the Explorers of Sky ROM file in your file system.

- Click the nds unpack button to unpack the ROM. This should take a few seconds to complete. Occasionally DSLazy fails to show that unpacking has completed even if it completes successfully. If unpacking takes longer than a few seconds, check the next step anyway to see if the files were unpacked.

- DSLazy will open File Explorer with a folder containing the unpacked files. This folder is named

NDS_UNPACK, and is placed in the folder that DSLazy is in.

Using ndstool

- Download ndstool (the .tar.bz2 file) and open the archive.

- Open a terminal and

cdto the extractedndstool-2.1.2folder, then run./configure && make && make install.- Depending on your permissions, you may need to run

sudo make installinstead ofmake installto run the installation with admin privileges.

- Depending on your permissions, you may need to run

- Create a folder to store the unpacked ROM files, then

cdto it. - Run

ndstool -9 arm9.bin -7 arm7.bin -y9 y9.bin -y7 y7.bin -d data -y overlay -t banner.bin -h header.bin -x <ROM path>, where<ROM path>is the file path to the Explorers of Sky ROM on your file system. This will unpack the ROM into the folder you created.

Setting up Ghidra

Analyzing a function in Ghidra

Ghidra is a free open-source reverse engineering tool developed by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). Ghidra can analyze binary data such as a game ROM to output assembly and even decompiled C, which we can read to reverse engineer a game. This kind of analysis occurs without the game running; this is known as static code analysis (as opposed to dynamic code analysis when debugging the game while it is running).

Ghidra is an ideal code analysis and disassembly tool for hobbyists, costing nothing for a fully featured application. There are paid alternatives to Ghidra; the industry standard for professional reverse engineering is IDA. However, the full version of IDA costs thousands of dollars and is too costly for many hobbyists, while the free version doesn’t have enough features for our purposes.

To install Ghidra, follow the instructions on Ghidra’s website.

If you’re on a recent version of macOS, you’ll need to give Ghidra’s decompiler permission to run before setting up a project. Inside Ghidra’s folder, go to Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/os/mac_x86_64, right-click the decompile executable file, select Open, and confirm the Open when macOS warns about not being able to verify the developer.

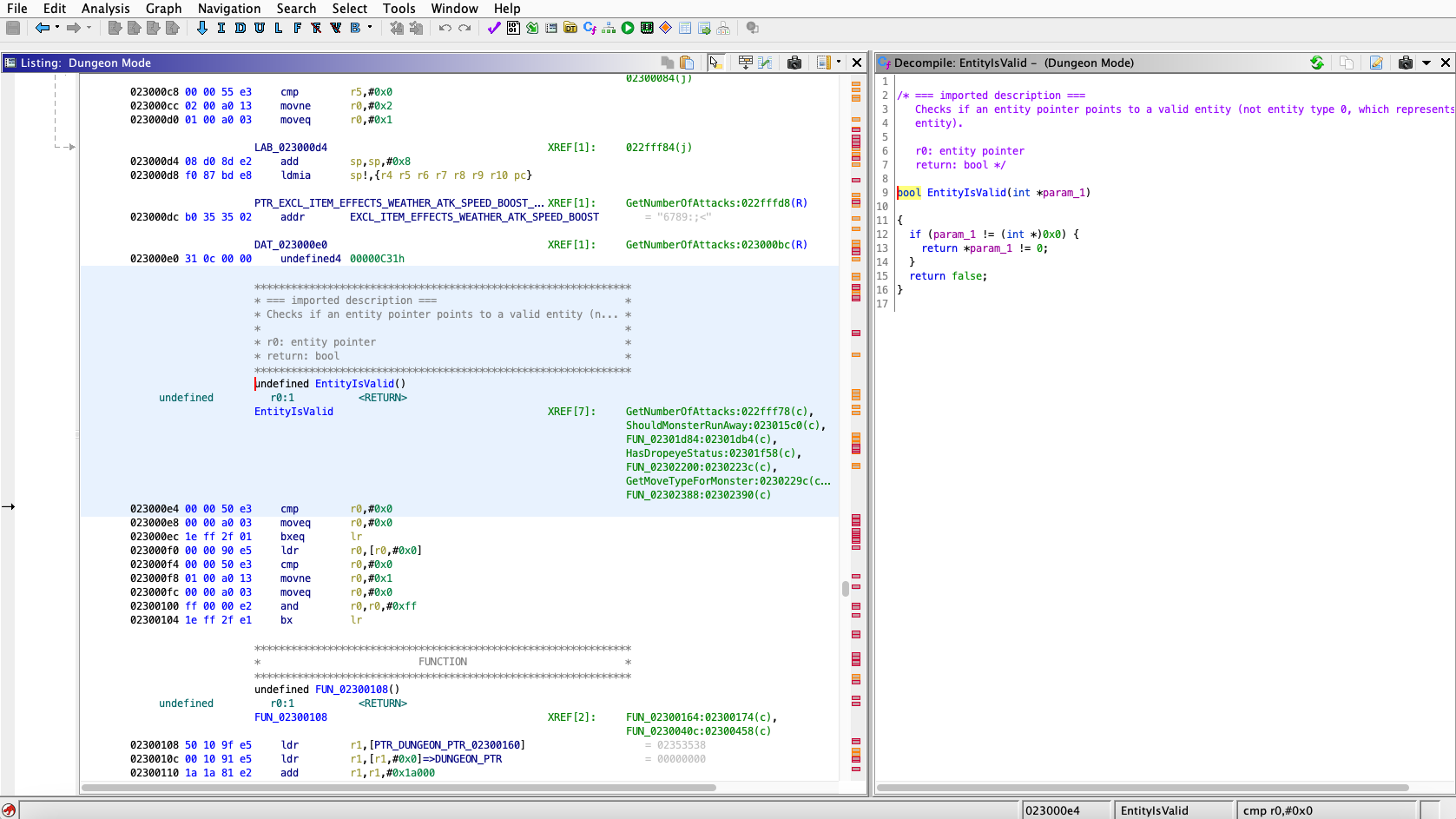

Launch Ghidra after it is installed, and you’ll see this screen.

Ghidra start screen

Creating a Ghidra project

Let’s make a new project using the Explorers of Sky ROM files that you unpacked.

- File > New Project…

- The project defaults to a “Non-Shared Project”. Click Next.

- Choose a project name and a directory to save the project, then click Finish.

- File > Import File…

- Choose the

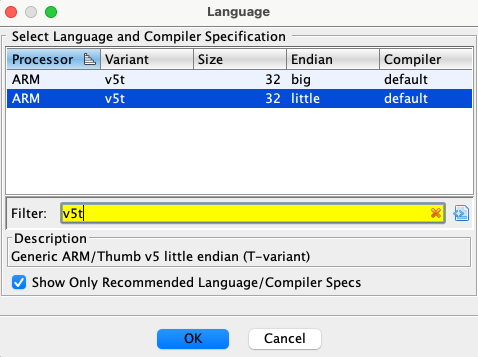

arm9.binfile from the unpacked Explorers of Sky ROM files. - Select an instruction set architecture (Language) for Ghidra to use for analyzing the binary. The DS uses the ARMv5T (technically ARMv5TE) instruction set in little-endian format (ARM:LE:32:v5t), which you can find by searching for “v5t” in the language select, then selecting the option with “little” under the Endian column.

Selecting the ARMv5T language - Click Options… and set the Base Address to 02000000.

- Click OK to make Ghidra inspect the binary.

- Once done, Ghidra will display a report with some details about the inspection. Click OK to continue.

- Double-click the ROM in Ghidra to open Ghidra’s code viewer.

- Ghidra will offer to analyze the binary. Click No for now, as there some more setup to do first.

If you do run an analysis at this point, it won’t cause any ill effects. Ghidra will simply run a partial analysis with what it has, and you can rerun the analysis later when everything is set up.

- Click File > Add To Program, then look for the

overlaysfolder in the unpacked ROM files. Chooseoverlay_0029.bininside this folder. - Click Options…

- Set the block name to “overlay_0029.bin”.

The block name won’t affect analysis and can technically be whatever you like. I recommend the same name as the overlay file to keep track of it.

- Set the base address to 22DC240.

- Click OK to confirm the options you set, OK to add the overlay, then OK when Ghidra presents the results of adding the overlay.

You may have noticed an Overlay checkbox in the options, but this isn’t helpful for our use case despite its name. Leave it unselected to avoid messing up Ghidra’s analysis.

- Repeat steps 12-16 with the overlay file

overlay_0010.bin. Use 22BCA80 for the base address of this file. - Repeat steps 12-16 with the overlay file

overlay_0031.bin. Use 2382820 for the base address of this file. - Run analysis by selecting Analysis > Auto Analyze ‘<project>‘…, or use the hotkey ‘a’.

- Use the default analysis settings and click Analyze.

- Wait for Ghidra to analyze the binaries. This may take a couple minutes.

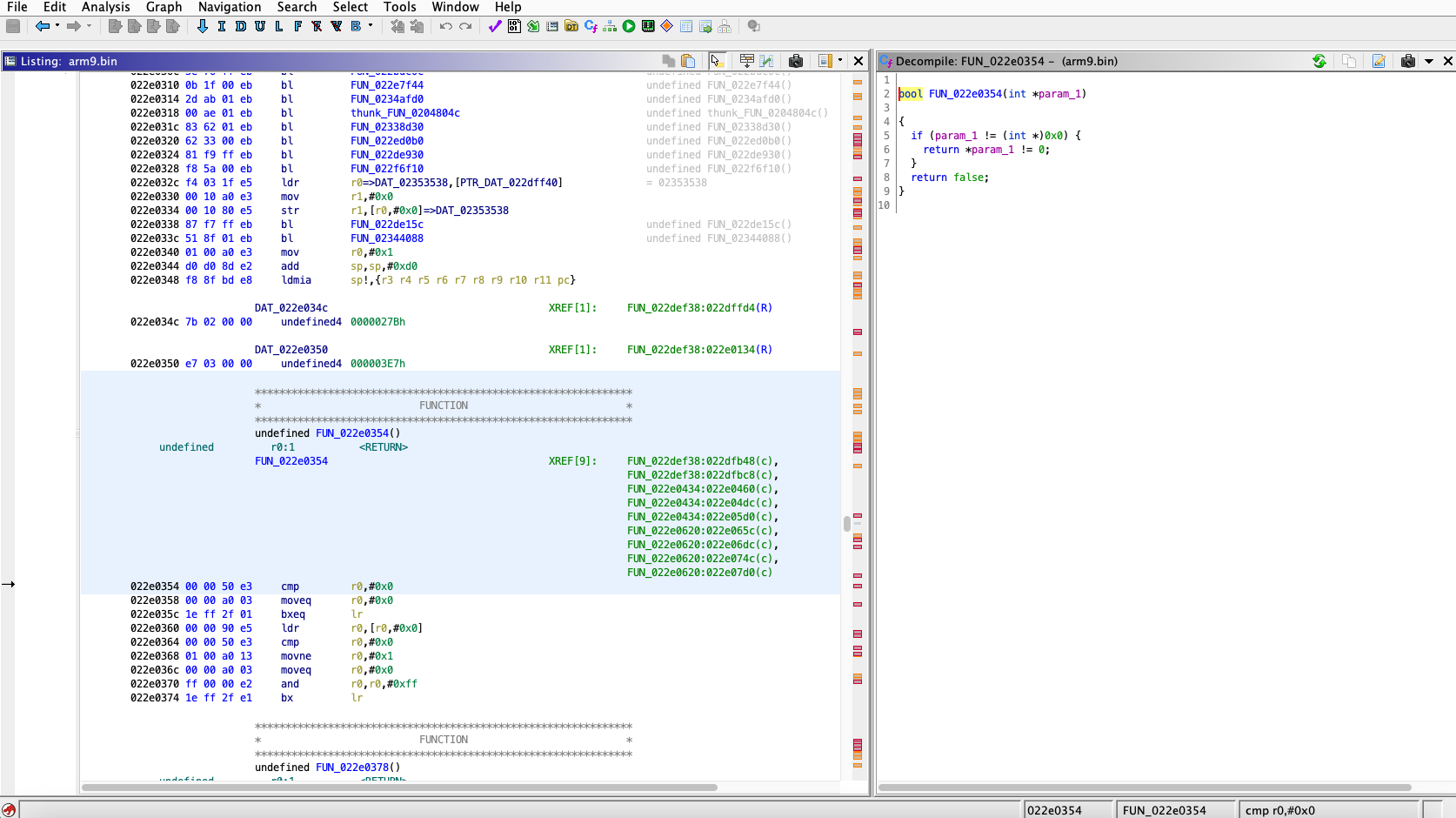

- When Ghidra’s analysis finishes, verify whether Ghidra was set up properly. Press ‘g’, enter the value “22E0354”, then press OK. You should see a screen like the image below. At this point, Ghidra is set up to start reverse engineering the game.

Ghidra’s auto-analysis of a function after setup

Setup considerations

How would you know to use the ARM:LE:32:v5t language if I didn’t tell you? First search for which CPU the DS uses; you’ll find that it uses the ARM946E-S and ARM7TDMI CPUs (e.g., from Wikipedia). From the tech specs of the DS, you’ll find that the ARM9 CPU is the CPU used for gameplay mechanics. Knowing the CPU, you can look for which language/architecture the CPU uses; ARM’s documentation states that the ARM946E-S uses the ARMv5TE architecture. This means the ARMv5T architecture is what we’re looking for. The “E” in “ARMv5TE” is a suffix that indicates support for additional signal processing instructions, though you won’t need to worry about those here.

As for endianness (the order that bytes are stored for each word of data), most ARM CPUs are “bi-endian” and support both little and big endian. In practice, most ARM programs use little endian. If Ghidra spits out incomprehensible disassembled code while using a little endian language, try big endian and see if the output is any better. Note that some CPUs, such as those using the PowerPC instruction set (e.g., the Wii), are predominantly big endian instead.

The project setup uses some magic numbers when adding overlays. Overlays will be discussed later in this tutorial, including how to find these numbers by yourself.

Some games compress arm9.bin and overlay files, which can be uncompressed using this compression tool. In Explorers of Sky’s case, the assembly files are not compressed, so you don’t need to worry about uncompressing them.

Setting up DeSmuME with Explorers of Sky

In addition to Ghidra, you’ll need to set up a DS emulator and progress the game past the opening sequence.

- Download the latest stable release of DeSmuME from DeSmuME’s website and extract it to the folder of your choosing.

- Open DeSmuME, go to File > Open ROM…, and select the Explorers of Sky ROM in your file system. Make sure to use the original ROM (.nds) file, not the files you unpacked from it.

- View and configure button mappings at Config > Control Config if needed.

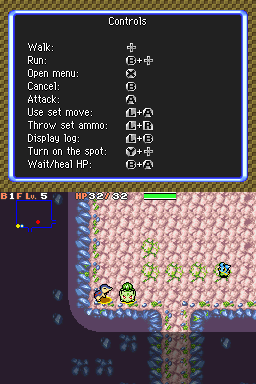

- Watch the intro cutscene for the game, then start a new game.

- The start of the game consists of a personality quiz that will decide your player character. Answer the questions, honestly or not, then the game will assign you a Pokémon.

- Choose a name for yourself, a partner Pokémon, and a name for your partner.

- After deciding your player and partner Pokémon, you will be taken to a cutscene. After the cutscene, you will enter the first dungeon of the game, Beach Cave.

- Once you enter Beach Cave, you are set up to reverse engineer the game.

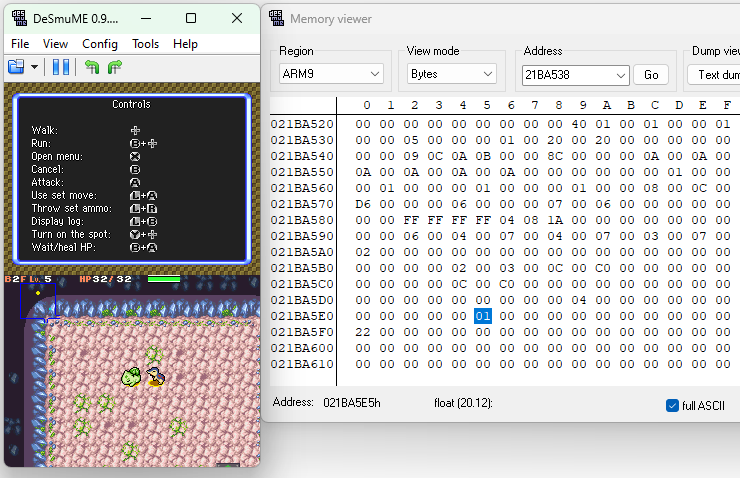

Explorers of Sky after setting it up

With both Ghidra and the game set up, the next step is to open up the game and read the code. You’ll need to know how to read assembly for this, which the next section will introduce.

Assembly primer

An assembly language (assembly or ASM for short) is a type of low-level programming language that closely matches the raw binary instructions (machine code) read and executed by the computer. Compared to a higher-level language like C, assembly uses fewer abstractions. For instance, a function call is a single-line statement in C, but this operation corresponds to several lines of assembly code. We’ll go into specific examples of this later on.

This tutorial presents a brief introduction of assembly to get you started. For brevity, I’ll be skipping some of the finer details. If you’re interested in a more thorough DS assembly reference, check out Tonc’s Whirlwind Tour of ARM Assembly.

Different CPUs may use different assembly languages depending on which operations the CPU supports (the instruction set of the CPU). While all CPUs support the minimum set of instructions required for a computer to function, extra instructions act as shortcuts that allow a program to compile to fewer lines of assembly, resulting in faster program execution in exchange for more complicated CPU hardware to support the additional instructions, and possibly instructions taking more space to store. This tutorial will use the ARM instruction set, as this is the main instruction set used by Explorers of Sky’s code. Future uses of the word “assembly” in this tutorial will be shorthand for “ARM instruction set assembly language”; this is a common shorthand in the context of a specific game.

In addition to ARM, the DS’s CPU supports another instruction set known as THUMB, which has less complicated instructions than ARM, but requires more instructions to accomplish the same functionality as ARM. Many DS games, like Explorers of Sky, use mainly ARM code, though some DS games make heavy use of THUMB. While the THUMB instruction set is out of the scope of this tutorial, it is fairly easy to learn once you know the ARM instruction set.

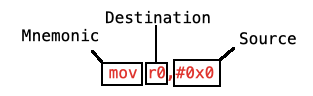

Here is a simple assignment instruction in assembly.

mov r0,#0x0

This statement assigns the number 0 (#0x0) to r0. r0 is one of the CPU’s registers. What are registers? Let’s talk about that first.

Registers

A register is a location in the CPU hardware that stores a value. When the CPU needs to store data for later, the registers are the fastest place to store and retrieve the data. Every assembly operation interacts with the registers in some way.

CPUs have a handful of registers available. In ARM CPUs, registers are named with the format rX, where “X” is the 0-indexed register number. The DS’s CPU has 16 registers numbered from r0 to r15, and each can store up to 32 bits (4 bytes) of data for a total of 512 bits (64 bytes) of data.

r15 is a special register called the program counter (PC for short). This register holds the address to the next instruction to be loaded, and is incremented by 4 automatically after an instruction is loaded (instructions are 4 bytes long). This causes assembly to be executed line-by-line. It is possible to set the PC’s value, which will cause the CPU to jump to the new address and begin executing code there; this is used for constructs like conditional statements, loops, and function calls. The CPU loads instructions slightly ahead of when it executes them, so the PC may be a few instructions ahead of the instruction currently being executed.

Some of the other registers also have special names and purposes. We will get into those later.

Memory

Register capacity is limited, so if a program needs to store more data than the registers allow, the data goes to main memory, also known as RAM (random-access memory) or simply memory. Storing and accessing memory is slower than using registers, but memory has a much larger capacity. The DS has 4 megabytes of RAM for regular code operations to use, and also has additional reserved RAM for special operations like I/O.

ROM

The ROM (read-only memory) file used to load the game is effectively an array of bytes. These bytes encode assets like sprites and audio, data values used by the game’s logic (e.g., the amount that a certain healing item will heal the player by), and code used to run the game.

When talking about data in the ROM, it is typical to refer to a piece of data according to its 0-indexed address (offset) from the start of the ROM. For example, the first byte in the ROM file is at address 0x0, and the 5th byte in the ROM file is at address 0x4. Addresses are almost always written in hexadecimal; the “0x” indicates that a value is expressed in hexadecimal format. Hexadecimal is also commonly used for other values in reverse engineering contexts.

Accessing ROM directly is relatively slow, so the DS loads ROM into memory before executing code and reading data from it. The area of memory containing ROM data is often called “ROM” despite technically being part of memory/RAM. There is not enough space in memory to load the entirety of ROM at once, so only portions of ROM can be loaded at a time.

Overlays

Overlaying is a design pattern that allows a computer to run a program that is larger than the computer’s memory capacity. The program’s code is separated into chunks known as overlays, and only a subset of overlays is loaded into memory at a time. As the state of the program changes and different overlays are required, the computer swaps out the overlays in memory that are no longer needed in exchange for the overlays that the program now needs.

The DS loads each overlay to a specific area of memory. Some overlays may overlap in memory, but they can only overlap if the two overlays will never be loaded together.

Explorers of Sky has 36 overlays. The code that handles gameplay inside dungeons is stored in overlays 29 and 31, while the code that handles cutscenes and overworld movement is stored in overlay 11. Both dungeon and overworld gameplay require overlay 10, so this overlay is loaded for both of these modes. Overlay 29 is loaded to address 0x22DC240, overlay 10 is loaded to address 0x22BCA80, and overlay 31 is loaded to address 0x2382820.

In-game, values in an overlay are accessed using their address within the overlay file plus the overlay file’s address. For example, the data at address 0x4 in overlay_0029.bin is accessed in-game using address 0x22DC244 (0x4 + 0x22DC240).

The exceptions to overlays are arm9.bin and arm7.bin. These contain the game’s core systems, such as the code needed to load overlays, and thus are never unloaded. arm9.bin is loaded at address 0x2000000, while arm7.bin is handled by the DS’s secondary ARM7TDMI CPU. You’ll probably not need to worry about arm7.bin unless you’re looking into the specialized processes it is responsible for, such as audio.

During Ghidra setup earlier, you set the Base Address of

arm9.binto 0x2000000, and the overlay files to their respective addresses. This matches where the DS loads the ROM files in memory, and supplying these address to Ghidra helps it to better analyze the code.

Each subset of overlays that can be loaded requires you to reimport arm9.bin as a new file in your project. The Ghidra setup from earlier set you up for reverse engineering the dungeon gameplay of Explorers of Sky, loading arm9.bin and adding overlays 10, 29, and 31. If you wanted to analyze overworld gameplay, you’d reload arm9.bin and add overlays 10 and 11.

Finding overlays

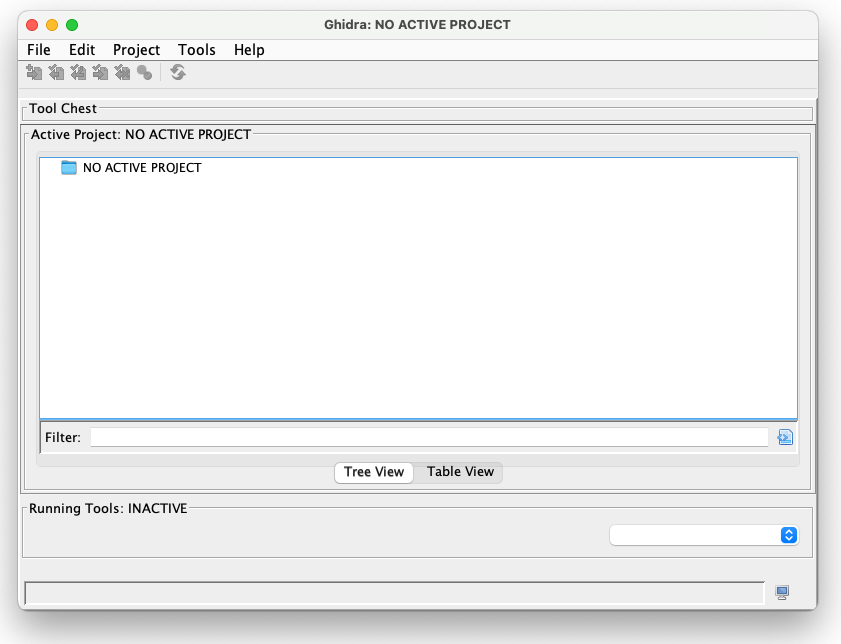

The starting addresses of each overlay in memory are defined in a file within the ROM called the overlay table (OVT). The overlay table is the file y9.bin in the files unpacked from the ROM. You can open this file with a hex editor like HxD (Windows) or Hex Fiend (macOS).

Inside y9.bin, each overlay is listed in order, starting with the overlay number, then the address, then some other information such as the size of the overlay, and finally 4 bytes (i.e., a word) of 0s as a delimiter between overlays. To find the starting address of an overlay, look for an occurrence of the overlay’s number that follows 00000000, then look at the next word to find the overlay address. The overlay address is in little endian, so read the bytes backwards (e.g., 80CA2B02 in little endian is equal to 0x022BCA80).

The overlay table for Explorers of Sky, with overlay 10 (0xA) highlighted. Overlay 10’s address is 80CA2B02 (0x022BCA80).

Once you know the address of an overlay, you can run the game, look at the overlay’s address in memory, and compare this with the start of the overlay file to see if the bytes match up. If they do, then that overlay is currently loaded in memory.

Most games have a place in memory that lists which overlays are currently loaded. For example, Explorers of Sky’s loaded overlays list is at address 0x20AF230. However, the location of this list is not standardized between games. Finding the list is non-trivial and outside the scope of this tutorial, though if a game’s reverse engineering community has already found it, it can simplify the task of finding which overlays are of interest to you.

Instructions

Instructions are used to manipulate data in registers or memory. The CPU executes instructions in sequence according to the value of the program counter.

Each instruction is encoded in 4 bytes of data. When encoded as bytes, the instruction is considered to be in binary code or machine code. Reverse engineering tools can read these bytes and convert them to a more human-readable form, assembly code.

Assignment

Here is the assignment instruction shown earlier:

mov r0,#0x0

There are three parts to this instruction:

- Mnemonic: The shorthand name of the operation to be performed. A

movinstruction assigns a value to a register. - Destination: The register to set the value in. In this instruction, the value of

r0will be set. - Source: The place to retrieve a value to store at the destination. In this case, the value is a constant value of 0; this is known as an immediate value in assembly nomenclature.

Combining all three parts, this instruction sets r0 to a value of 0, discarding the previous value that was in r0.

It is also possible for the source to be another register. The following instruction will copy the value of r1 into r0.

mov r0,r1

Arithmetic

Let’s look at a different kind of instruction. The instruction below is an addition operation.

add r0,r1,#0x1

This instruction add 1 to the value in r1 and stores it in r0.

r0 is the destination register like before. Since addition requires two operands, there are two sources, r1 and #0x1. It is possible to add either a register and an immediate value, or two registers. If the instruction uses an immediate value, the immediate value must always come last; this constraint has to do with how the instruction is implemented in the CPU’s hardware.

In the special case where you want to add an immediate value to a register value and store the new value back in the same register, you can use the following shorthand.

add r0,#0x1

This will add 1 to the value of r0 and store the sum in r0. Alternatively, you can say that this increments the value in r0.

Other available math operators include subtraction, multiplication, negation, bitwise AND/OR/XOR/NOT, and logical/arithmetic (unsigned/signed) left/right bit shifts. Some of these operations are more rigid than addition, such as not supporting immediate values, though they all follow a similar structure. For a full list of supported instructions, refer to ARM’s developer documentation.

You may notice the lack of a division instruction. Division with arbitrary numbers is more complicated than the operations listed above, so it is implemented as a function rather than a single instruction. This means division is much slower than other math operations. Note that the right shift operator can divide numbers by powers of 2 to achieve certain divisions in a single instruction.

If both sources are registers, ARM also supports bit-shifting the second source register and using the shifted value for the instruction.

add r0,r1,r2, lsl #0x2

This will left-shift r2 by 2 (i.e., multiply by 4) before the addition operation, equivalent to r0 = r1 + r2 * 4.

Load/Store memory

Registers can only store a handful of values, so memory is used to store the majority of a program’s data. As a reminder, memory (also called main memory or RAM) is where most data is stored given that registers have limited storage capacity.

Here is an instruction that stores to memory.

str r0,[r1,#0x4]

- The mnemonic “str” stands for “store register”.

r0is the source register, containing the value to store in main memory.- The bracketed values

r1(register) and#0x4(can be immediate value or register) are added together, and the sum is the address in main memory to store the value in. The immediate value can be 0 to store the value directly to the address inr1.

For example, if r0 is 3 and r1 is 0x2000000, the value 3 will be stored to memory address 0x2000004 (0x2000000 + 4). Since a register value is 4 bytes long, the full value be stored in memory addresses 0x2000004 to 0x2000007 (inclusive).

Alternate instructions strh and strb are used to store the lowest 2 bytes (halfword) and 1 byte of the source register, respectively.

Loading from memory uses a similar format, except data flows in reverse.

ldr r0,[r1,#0x4]

“ldr” stands for “load register”. This command loads from the address stored in r1 plus the immediate offset of 4, storing the loaded value in r0. Like str, there are instructions to load halfwords (ldrh) and single bytes (ldrb).

In addition to load from a register address, ldr can also load hard-coded values in the assembly code. These are marked with DAT_<address> in Ghidra, where <address> is the address of the value in the ROM.

ldr r0,[DAT_02090fe8]

...

DAT_02090fe8

02000010

This will load the value 0x2000010 into r0.

Ghidra marks data values with

DAT_<address>for convenience. Under the hood, theldrinstruction contains a signed 13-bit offset from the instruction’s address in ROM to the data value’s address.

Branches

All the instructions covered so far are executed line-by-line in order. The program executes an instruction, increments the program counter by 4 (the number of bytes per instruction), executes the next instruction in memory, and so on. For example, if the program counter starts with a value of 0x2000000, program execution is as follows:

- Execute the instruction at address 0x2000000.

- Increment the program counter to 0x2000004.

- Execute the instruction at 0x2000004.

- Increment the program counter to 0x2000008.

- Execute the instruction at 0x2000008.

And so on.

Branches, also known as conditionals or jumps, are instructions that set the program counter to a specific value, causing program execution to jump to the specified instruction.

Here is an unconditional branch instruction.

b LAB_02090fdc

LAB_02090fdc is known as a label. The label represents a certain instruction in memory; in this case, the label refers to the instruction at address 0x2090FDC in the ROM.

Taking the previous example, if the branch instruction above is at address 0x2000004:

- Execute the instruction at address 0x2000000.

- Increment the program counter to 0x2000004.

- Execute instruction

b LAB_02090fdcat 0x2000004. - The branch instruction sets the program counter to 0x2090FDC.

- Execute the instruction at 0x2090FDC.

- Increment the program counter to 0x2090FE0.

- Execute the instruction at 0x2090FE0.

And so on. After branching, the program counter resumes incrementing and executing instructions in order.

Like with data values, the branch instruction contains an offset from the instruction’s address under the hood to determine where to jump to. For branch instructions, the offset is 26 bits long.

In addition to the b instruction, there are other unconditional branch instructions for certain cases:

bl: Branch instruction used to call functions, which will be discussed later.bx: Branch to an address stored in a register.

Conditional branches

It is possible to have branch instructions that only execute if a condition is satisfied. If the condition is not satisfied, the conditional branch instruction is skipped, and the program counter increments and continues to the next instruction.

A conditional branch consists of two instructions. Here is an example.

cmp r0,#0x1

beq LAB_02090f14

With this set of instructions, if the value of r0 is equal to 1, then the program branches to LAB_02090f14. If r0 is not equal to 1, then the program skips the branch and moves to the next instruction instead.

- The

cmpinstruction is used to set up a conditional branch by comparing two values. The first value is always a register, and the second value can be either an immediate value or another register. - All conditional branch instructions start with the letter ‘b’ and end with a mnemonic extension, also known as a conditional code, that specifies what kind of condition needs to be met. In this case, the extension

eqsignals that the branch will be taken if the compared values are equal.

All basic comparison operators are supported by conditional branch instructions:

- Equal:

beq - Not equal:

bne - Greater than:

bgt,bhi - Greater than or equal:

bge,bcs - Less than:

blt,bcc - Less than or equal:

ble,bls

Equality and non-equality have a single instruction each, while the other comparison operators have different versions to support unsigned integer, signed integer, and floating-point comparisons. A full list of the conditional codes for each comparison operator can be found in ARM’s developer documentation.

ARM also has a shortened form of conditional branching for singular instructions.

cmp r0,#0x1

moveq r0,r1

Like with normal conditional branches, a cmp instruction is used to set up the branch. After cmp, the next instruction is not a b instruction, but rather a different instruction followed by a conditional code. In the above example, r0 is assigned to r1 only if r0 is equal to 1. All instructions allow conditional codes to be attached to them.

A higher-level language like C uses conditional keywords like if/else if/else and looping keywords like while/do while/for. These constructs typically translate to conditional branch statements when compiled to assembly.

Internally, the

cmpinstruction sets four 1-bit condition flags in the CPU, named C, N, V, and Z. Each conditional branch instruction checks specific condition flags to decide whether to branch. For example, thebeqinstruction will branch if the Z flag has a value of 1. Chances are that you won’t need to interact directly with these condition flags; knowing the conditional codes is sufficient.

Functions

Conceptually, functions in assembly work similarly to functions in higher-level languages. A function can be invoked/called, which will cause the function to run before returning back to the code that called the function. Functions can also have parameters and return values. Let’s look closer into how functions work in assembly.

A function can be called as follows:

bl FUN_022de288

bl is a special branch instruction used for functions. In this case, the program will jump to the first instruction of the function FUN_022de288. Before branching, the current value of the program counter is saved to the link register (lr), which corresponds to r14 for the DS’s CPU. The link register’s value will be retrieved at the end of the function to return the program to the place where the function was called.

Here is a simple function:

FUN_022de288

ldr r0,[r0,#0x0]

bx lr

By default, Ghidra names functions according to the memory address where they start at. This function starts at memory address 0x22DE288, so the function is named FUN_022de288.

Most functions have three parts: a prologue, a body, and an epilogue. The prologue and epilogue consist of standard setup and cleanup for function execution, while the body is the main logic that the function will execute. In the function above:

- The function is simple enough to have no prologue.

- The body consists of the instruction

ldr r0,[r0,#0x0]. - The epilogue contains the instruction

bx lr. This will set thepcto the value inlr, which causes the program to return to the place that called the function.

Once the function returns from the epilogue to the caller function, the pc is incremented as usual, causing the program to continue at the instruction directly after the function call.

Function arguments/parameters

To pass arguments into a function, the arguments are stored in registers before calling the function. r0-r3 are used to pass arguments; if the function requires more than four arguments, any further arguments are pushed onto a place called the stack, which will be discussed later on.

In the code below, a value is assigned to r0 to pass as an argument into FUN_022de288.

...

add r0,r4,#0x0

bl FUN_022de288

Once inside the function, the function can use the argument from r0.

FUN_022de288

ldr r0,[r0,#0x0]

...

Return values

If a function needs to return a value, the return value will be stored in r0 just before the function returns. The caller function can use the return value in r0 as needed.

In function FUN_022de288, the function body assigns a value to r0 before returning with bx.

FUN_022de288

ldr r0,[r0,#0x0]

bx lr

The caller can call the function, then retrieve the return value from r0 to use for processing.

bl FUN_022de288

cmp r0,#0x1

...

Call stack

When a function is called, the caller is likely already using the registers to store values. There are only a handful of registers, and the function may also need those registers to do its work. Before the function can use the registers, it should save the existing values of registers it plans to use. When the function is finished, it should restore the saved values back to the registers so the caller doesn’t lose its current state when it resumes execution.

Registers r0-r3 and r12 are designated as scratch registers, which are not saved by a function that uses them. Registers r4-r11 are preserved registers (or variable registers) whose values are saved and restored by the function. lr is also saved if the function calls other functions.

Since a function can call another function, which can itself call another function and so on, every function must store and restore the register values at the proper times. This is accomplished using a place in memory called the call stack.

The call stack, often shortened to stack, is a special place in memory used to save register values when functions are called. It is also used to store local variables if there are too many for the registers to hold. As the name implies, it is a last-in first-out (LIFO) data structure. The address at the top of the stack is tracked using r13, often called the stack pointer (sp).

One of the main purposes of the function prologue is to save register values to the stack. Register values are pushed onto the top of the stack (i.e., the address of sp) using the stmdb (“store multiple, decrement before”) instruction, also known as push. This instruction is used to store multiple register values at consecutive addresses, and it achieves this by decrementing the stack pointer, storing the first value, decrementing the stack pointer again, and so on.

Here is an example prologue that saves register values.

stmdb sp!,{r4 lr}

This prologue is taken from a function that uses r4 in its calculations. The function also calls another function with bl, which will overwrite the existing value in lr. Therefore, the function must save the current values of r4 and lr in the stack.

In the function epilogue, saved register values are restored to their saved values by using the ldmia (“load multiple, increment after”) instruction, also known as pop. This is the corresponding epilogue to the prologue above.

ldmia sp!,{r4 pc}

ldmia will remove the values at the top of the stack and assign them to the specified registers. ldmia also increments sp to move the top of the stack past the items that were popped off. In the example above, r4 is assigned back to its original value. The pc is assigned to the value originally stored from lr, a shortcut to make the program jump back to the caller function.

In addition to saving and restoring register values, the stack is used for a couple other purposes.

Stack local variables

If a function has many local variables or large local variables like structs or arrays, it may run out of registers to store all the variables. If this happens, the excess values are stored in the stack. An occurrence of this may look like the code below.

sub sp,sp,#0x1c

...

str r0,[sp,#0x4]

...

add sp,sp,#0x1c

In the function prologue, the stack pointer is subtracted by 0x1c to make room for local variables. The function stores and loads local variables on the stack by using an offset from sp. In the function epilogue, the function cleans up the allocated local variable space by adding back to sp.

In Ghidra, stack local variables are assigned names such as local_24 based on their position in the stack, rather than displaying the raw offset from sp. The number is derived by taking the total size of the local variable region (0x1c) and subtracting the offset of the variable (0x4), before converting to decimal. 0x1c - 0x4 = 0x18 = 24.

Stack function arguments

There are four registers allotted for passing arguments into a function. If the function needs more than four arguments, additional arguments are passed by storing them on the stack. The stack is also used for passing larger data types such as structs and arrays.

Below is an example of passing five arguments into a function.

// Prologue

sub sp,#0x4

...

// Body

str r2,[sp,#0x0]

add r0,r5,#0x0

add r1,r4,#0x0

mov r2,r9

add r3,r6,#0x0

bl FUN_02332bac

...

// Epilogue

add sp,#0x4

Like with stack local variables, the prologue subtracts from sp to allocate stack space for passing a function argument on the stack. When the function FUN_02332bac is called, r0-r3 are used for four of the arguments, and the stack is used for the last argument (set with str r2,[sp,#0x0]). The epilogue adds to sp clean up the stack space.

Inside FUN_02332bac, the function accesses the stack argument via an offset from sp.

FUN_02332bac

...

ldr r0,[sp,#Stack[0x0]]

...

The patterns above for passing arguments, returning values, saving registers, and allocating local variables are all part of the ARM calling convention, a set of standards for how assembly code should use registers and memory when calling functions to ensure correct execution of the program. If you write higher-level code like C, the compiler will generate assembly code that follows the calling convention. If you write assembly code by hand, there’s nothing stopping you from violating this convention, but deviating from the convention is bad practice and can easily lead to bugs.

Structs

By analyzing the assembly code, it is possible to tell when a struct from a higher-level language like C is compiled down to assembly.

In C, a struct definition may look like the following. For this tutorial, assume that int has a size of 4 bytes:

struct Position

{

int x;

int y;

}

This struct has a size of 8 bytes. Since x is the first variable defined in the struct, it is located at the start of the struct (i.e., an offset of 0). x takes up 4 bytes, so the following variable, y, has an offset of 4 from the start of the struct.

Typical assembly code maintains a pointer to the start of a struct, using offsets to access each of the struct’s fields. The following code is an example of storing values into a struct.

ldr r0,[DAT_02073b70] // Load the address of a Position.

mov r1,#0x6

str r1,[r0,#0x0] // position.x = 6;

mov r1,#0x4

str r1,[r0,#0x4] // position.y = 4;

Within reverse engineering communities, it is common to have a struct field whose purpose is not yet known. Unknown fields are often named by the community according to their offsets. For example, if the struct above was not yet identified as a struct that stores position data, it might use names like the following:

struct unkStruct

{

int unk0;

int unk4;

}

Copying struct data

A common operation with structs is copying values from one struct to another. There are special instructions for loading and storing values in bulk: ldmia and stmia. We’ve seen similar instructions when pushing and popping from the stack, but let’s look into them in more detail.

The ldmia instruction stands for “load multiple, increment after”, and looks like this:

ldmia r1!,{r3 r4 r5}

r1 contains the initial address to load data from. For each of the registers in brackets, 4 bytes of data will be loaded into the register from the address in r1, then r1 is incremented by 4. This results in 12 bytes of data from the address in r1 being loaded into the registers r3, r4, and r5.

For example, if r1 initially contains the address 0x2000000, the ldmia instruction will do the following:

- Load the value at address 0x2000000 to

r3. - Increment

r1to 0x2000004. - Load the value at address 0x2000004 to

r4. - Increment

r1to 0x2000008. - Load the value at address 0x2000008 to

r5. - Increment

r1to 0x200000C.

It is also possible to pass a range of registers to load into rather than listing each individual register.

ldmia r1!,{r3-r5}

The “!” in the instruction indicates “write-back mode”, which means the source register is incremented by the instruction. In some instruction sets, it is possible to omit the “!” to keep the source register unchanged.

The stmia instruction (store multiple, increment after) works similarly to ldmia, except it stores the value in each of the bracketed registers into an address. Like ldmia, stmia can take a list of individual register or a register range.

stmia r2!,{r3 r4 r5}

If r2 initially contains the address 0x2000000, the stmia instruction will do the following:

- Store the value in

r3to address 0x2000000. - Increment

r2to 0x2000004. - Store the value in

r4to address 0x2000004. - Increment

r2to 0x2000008. - Store the value in

r5to address 0x2000008. - Increment

r2to 0x200000C.

With both ldmia and stmia, the incremented register’s address ends up at the address immediately after the last value loaded/stored. This makes it possible to chain ldmia/stmia to copy data of any size. A chain of these instructions may look like the following:

ldmia r1!,{r3 r4 r5}

stmia r2!,{r3 r4 r5}

ldmia r1!,{r3 r4 r5}

stmia r2!,{r3 r4 r5}

These instructions copy 24 bytes of data from the address in r1 to the address in r2.

Using ldmia and stmia, copying data from one struct to another takes far fewer instructions than it would by copying each field individually.

Arrays

In assembly, there are several ways that array access can be implemented.

In several ways, arrays are similar to structs. If accessing a hard-coded array index (i.e., outside of a loop), offsets are used to access the data, similar to structs. Copying array data is also similar to copying structs, often using the same ldmia/stmia instruction chains.

If an array is accessed in a loop, it is still possible to use offsets, though the offset must be incremented or recalculated for each array element. The following example iterates through a size-5 array of 4-byte values (e.g., pointers).

ldr r2,[DAT_02073b70] // Load pointer to start of array.

mov r6,#0x0 // Initialize array index.

LAB_02073ac0

lsl r1,r6,#0x2 // Calculate array offset by left-shifting by 2 (multiplying by 4).

ldr r0,[r2,r1] // Load current array element.

... // Process current array element.

add r6,#0x1 // Increment array index.

cmp r6,#0x5

ble LAB_02073ac0 // Go back to loop start if iteration is not finished.

Alternatively, a pointer to the current array element can be initialized from the array pointer and incremented.

ldr r2,[DAT_02073b70] // Load pointer to start of array.

mov r6,#0x0 // Initialize array index.

LAB_02073ac0

ldr r0,[r2,#0x0] // Load current array element.

... // Process current array element.

add r6,#0x1 // Increment array index.

add r2,#0x4 // Increment current array element pointer.

cmp r6,#0x5

ble LAB_02073ac0 // Go back to loop start if iteration is not finished.

Switch statements

In assembly, switch statements are often implemented using a jump table. A series of b instructions are stored in assembly, and value passed into the switch statements is added to the pc to jump to the corrresponding b instruction, which will then jump to the logic for the case.

For example, let’s take a simple switch statement in C:

int type;

// Logic to assign type variable

switch (type)

{

case 2:

case 3:

case 5:

// Logic to handle case.

break;

case 0:

case 1:

// Logic to handle case.

break;

case 4:

// Logic to handle case.

break;

default:

break;

}

The switch statement above may look like the following in assembly:

// Logic to assign r0 (type variable).

...

cmp r0,#0x5

addls pc,pc,r1, lsl #0x2 // Multiply type by 4 to get jump table offset to branch instruction.

b switchD_02334050::caseD_6 // Go to end of function and do nothing if value is out of range.

switchD_02334050::caseD_0

b LAB_023344e8

switchD_02334050::caseD_1

b LAB_023344e8

switchD_02334050::caseD_2

b LAB_023344d0

switchD_02334050::caseD_3

b LAB_023344d0

switchD_02334050::caseD_4

b LAB_02334510

switchD_02334050::caseD_5

b LAB_023344d0

Some switch statements forgo a jump table and use a series of conditional branches instead, and sometimes both approaches are used in tandem.

Assembly primer wrap-up

If you’ve made it this far, you now have the baseline knowledge to read the DS’s ARM assembly code and identify some of the most common assembly patterns. While there are a number of less common assembly operations and patterns not covered in this tutorial, you should have enough context to fill in the gaps as needed with documentation such as the official ARM docs, Tonc, and your favorite search engine. Like most skills, practice is the best way to improve your assembly reading skills.

The next step is to explore the tools that will help with reverse engineering a DS game. We’ll start with our static code analyzer, Ghidra.

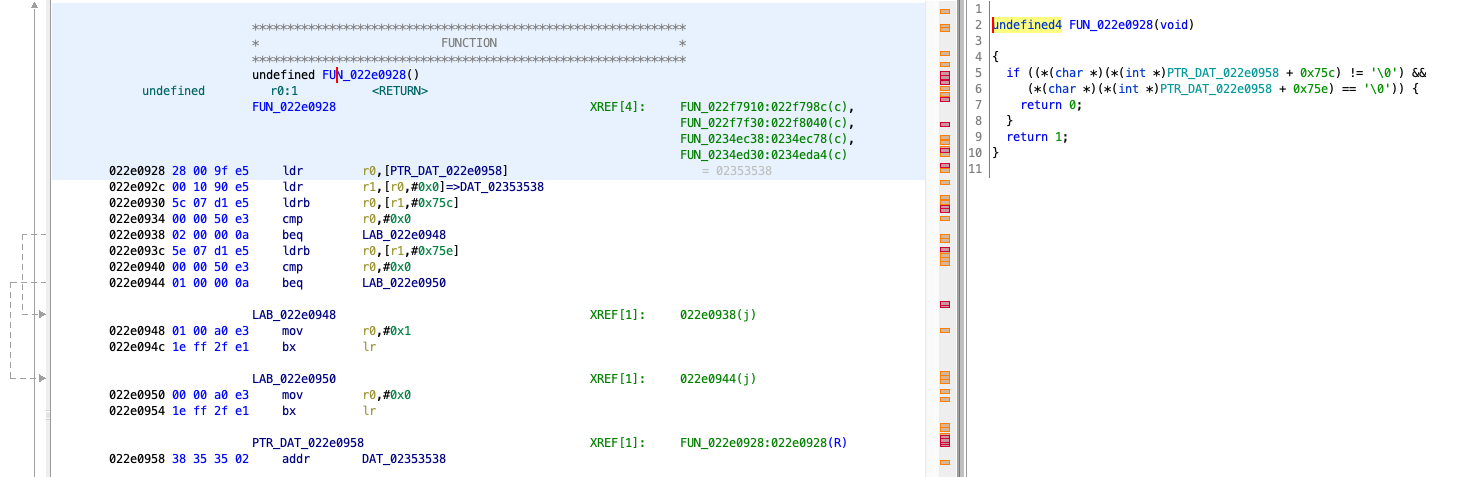

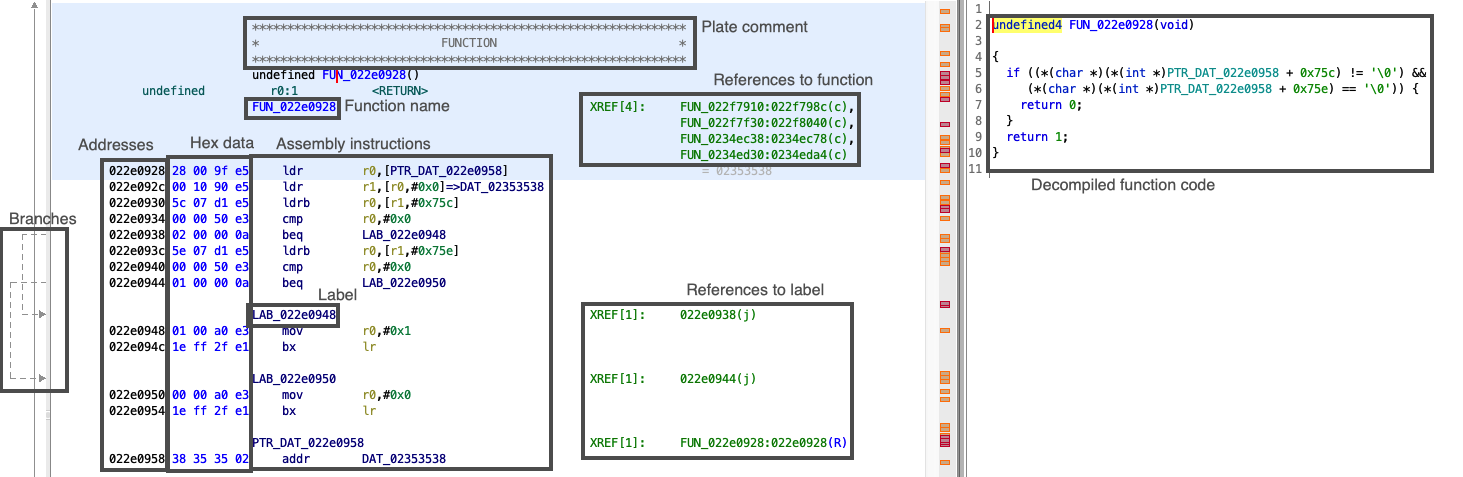

Using Ghidra

Ghidra is a powerful reverse engineering tool with a rich set of features. This section will go over some basic Ghidra usage to get you started with reading assembly.

The Ghidra interface looks like this:

There are two main areas of the Ghidra workspace that we will be using.

- The center window is the listing. This is where assembly code is displayed.

- The window on the right is the decompiler, which analyzes the assembly code for the currently selected function and decompiles it to C.

There are other windows in the Ghidra interface, but this tutorial will not go into them. You can close them to give more room to the listing window.

For this demonstration, we’ll use the function at address 0x22E0354. To navigate to this address, press ‘g’ and enter in “22E0354”. Scroll down a bit to see the whole function, which looks like this:

FUN_022e0354 in Ghidra

Let’s break down what is on the screen.

- Function name is self-explanatory.

- It is possible to add comments to the assembly code. A plate comment is a comment that takes up several lines. Ghidra automatically add a plate comment to denote functions, and it is possible to add more yourself (we’ll talk about that later).

- The references to function section lists all the places in the assembly code that call the current function. The list is in the format “function-name:instruction-address”. In this case, Ghidra found 4 places that call

FUN_022e0354, one of which isFUN_022f7910with ablinstruction at address 0x22F798C. - Assembly instructions is where the actual assembly code is, along with labels to denote branch destinations and hard-coded data values.

- Hex data contains the raw hexadecimal values in the ROM file that correspond to the assembly instructions. The

ldr r0,[PTR_DAT_022e0958]instruction at the start ofFUN_022e0354is derived from the hex value28 00 9f e5in the ROM. - The addresses contain the addresses/offsets of each instruction from the start of the file. The

ldr r0,[PTR_DAT_022e0958]instruction at the start ofFUN_022e0354is at address 0x22E0928 in the ROM. - The branches section contains arrows that denote branches in the function; the start of the arrow is the branch instruction, and the end of the arrow is the instruction that the branch will set

pcto. - References to labels lists the places that branch to each label. Listed here is the address of each branch instruction to a given label. For example,

LAB_022e0948is referenced by thebeqinstruction at address 0x22E0938. - The decompiled function code in the decompiler window contains decompiled C code for the function.

Decompiler

The decompiler is a tool that attempts to decompile assembly code into C code. Since C is a higher-level language than assembly, it is sometimes faster to read the decompiled C code than assembly code when figuring out how a function works.

With the existence of a decompiler, you may be wondering: what’s the point of learning to read assembly code if it can be decompiled to C?

- Since the C code is generated instead of manually written, it can be harder to read than the raw assembly code at times.

- The decompiler is not perfect, and sometimes it may fail to decompile the function.

- When debugging the game while it is running, you will be stepping through assembly code rather than C code.

- Depending on your goals with reverse engineering, it is often necessary to use assembly rather than decompiled C code. For example, if you want to make a patch to the game by changing the code, you must do this via assembly rather than C (unless the reverse engineering community for the game has created tools to inject compiled C code in the ROM, which is rare).

Treat the decompiler as another tool in the toolbox rather than relying solely on it. Chances are that you will switch between reading the raw assembly and reading the decompiled C code based on the current task at hand.

Navigation

There are several ways to navigate through code within Ghidra.

- As demonstrated before, pressing ‘g’ (Go To…) allows you to jump to a specific address in the ROM.

- Double-clicking on a function, label, or reference to a function/label will jump to the corresponding location in the ROM.

- On the toolbar at the top of the Ghidra window, there are buttons to navigate back and forward. These buttons keep track of your history when jumping to different addresses via Go To… or when clicking on functions and labels. You can hover over these buttons to see keyboard shortcuts for them (which may differ based on your OS).

Highlighting

Ghidra allows you to highlight certain corresponding elements, which are useful when visually inspecting the code.

- Clicking a line of assembly will highlight the corresponding line of decompiled C code. Likewise, clicking a line of C code will highlight the corresponding assembly code.

- Middle-clicking a symbol in Ghidra will highlight all occurrences of the symbol. For example, you can middle-click an occurrence of

r1in the assembly to highlight all other places wherer1is used. - Right-clicking a variable in the decompiler and choosing Highlight > Forward Slice or Highlight > Backward Slice will highlight all other variables whose data flows from/to the variable you selected.

Comments

You can add comments to the assembly code by right-clicking an assembly instruction and going to Comments in the context menu. There are options to position the comment in several places, including end-of-line (EOL), pre-line, post-line, and plate comments. The default keybind ‘;’ will open the comment interface for EOL comments, and you can also assign key bindings to the other types of comments in Edit > Tool Options > Key Bindings.

Here is an example end-of-line comment.

End-of-line comment

Liberal use of comments is highly recommended. There are no descriptive variable names in assembly, so it is easy to get lost if you don’t leave notes for yourself.

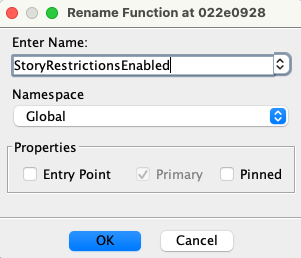

Label names

Once you figure out what a function, branch label, stack value, or data value does, you can rename it by right-clicking the label and clicking Edit label (hotkey ‘L’). You can also edit variable names in the decompiler.

Renaming a function’s label

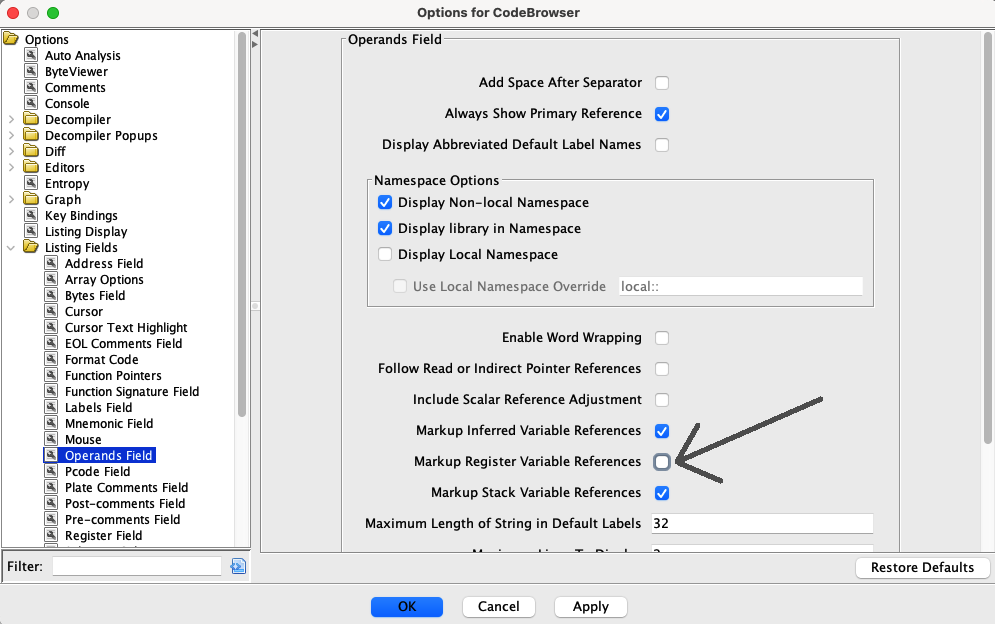

Sometimes Ghidra’s disassembler will automatically label registers as parameters. This is rarely helpful because registers are reused for many variables throughout the function. To remove these labels, go to Edit > Tool Options…, select Options > Listing Fields > Operands Field in the menu that opens, then uncheck Markup Register Variable References.

Disabling labels on registers

Ghidra wrap-up

By now, we’ve explored enough of Ghidra’s functionality to get started on reading the assembly code for a game. Ghidra has a ton of other useful features for reverse engineering, so you may wish to explore on your own and discover which features strike your fancy.

Ghidra is great for analyzing code while the game is not running. While this can go far on its own, it is useful to supplement this by analyzing code in action while the game is running. The next section will focus on the debugging capabilities of DeSmuME.

Debugging with DeSmuME

When reverse engineering, it is often useful to inspect the state of the game while it is running, a process known as dynamic code analysis. This includes looking at memory values, stepping through assembly code execution, and inspecting registers. This section will give a brief survey of some of the debugging capabilities that DeSmuME provides.

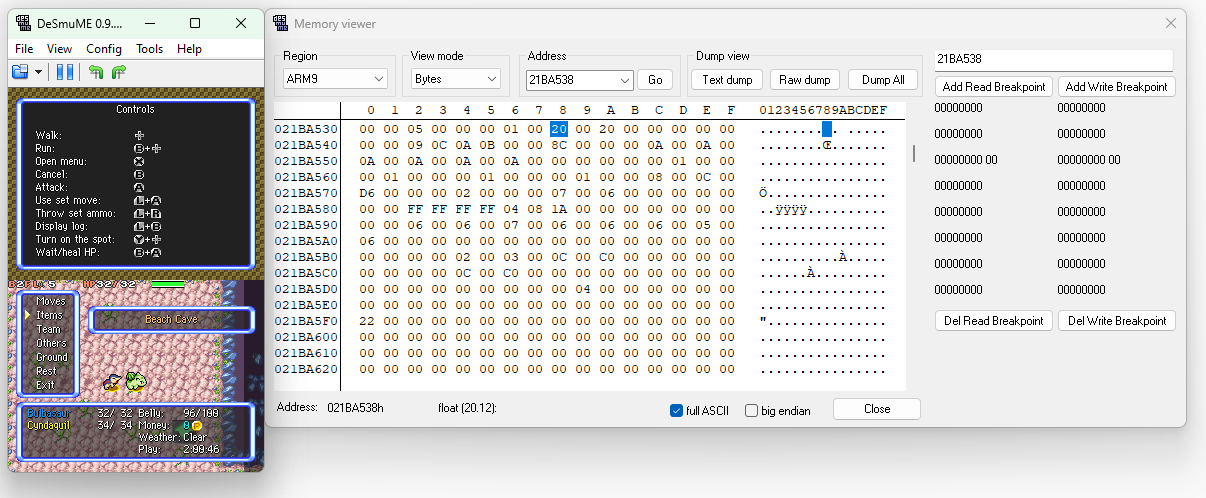

Memory viewer

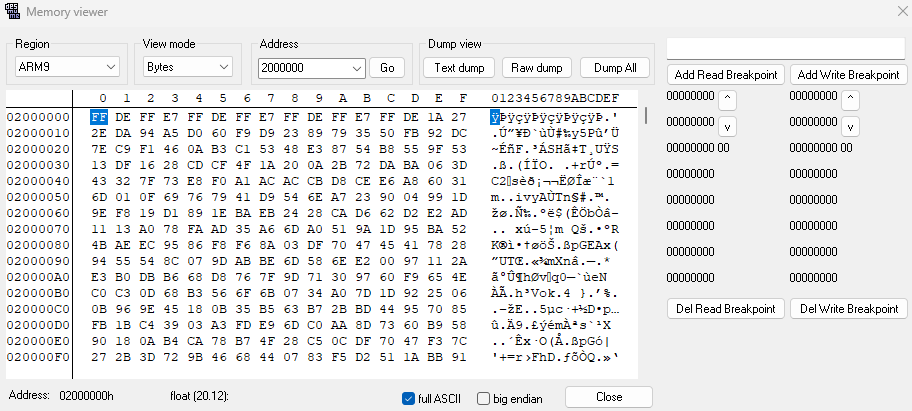

The memory viewer allows viewing and editing values in main memory. The memory viewer can be accessed at Tools > View Memory, and will bring up a window that looks like the image below. Note that you can select View Memory multiple times to open multiple memory viewer windows.

Memory viewer window

In the above image, the memory viewer shows the memory values from addresses 0x2000000 to 0x20000F0. Byte data is displayed in a tabular format, with the first digit of the address as the column and multiples of 0x10 as the rows. For example, row 0x2000010 contains the values from addresses 0x2000010 to 0x200001F, and the address 0x2000014 contains the value 0xD0. Single bytes are shown by default, and it is possible to change this view to halfwords (2 bytes) or words (4 bytes) to help display larger values such as 4-byte pointers.

To the right of the memory table is a string representation of the data. This can be useful when browsing portions of memory that are intended to represent in-game text, or to quickly browse for patterns in the data.

You can click on a byte value in the table to select it. This will show signed/unsigned integers representations (in decimal rather than hexadecimal) of the value at the bottom of the window. When a value is selected, you can also change the value, which will immediately be reflected in-game. Note that some values may immediately revert to the previous value if the game’s code sets the value every frame.

You can jump to any address in memory by entering the address into Address at the top, then pressing Go. The window will remember recent addresses you jump to.

For a demonstration of the memory viewer’s capabilities, jump to address 0x21CCB00, which contains data about the player and partner Pokémon. Certain values around this address constantly change, which represents values changing in-game. In this case, several of the rapidly changing values here control the animations of the Pokémon on screen. If you move around in-game, you’ll notice additional variables changing, which represent values such as the position of the Pokémon on the screen and on the dungeon floor.

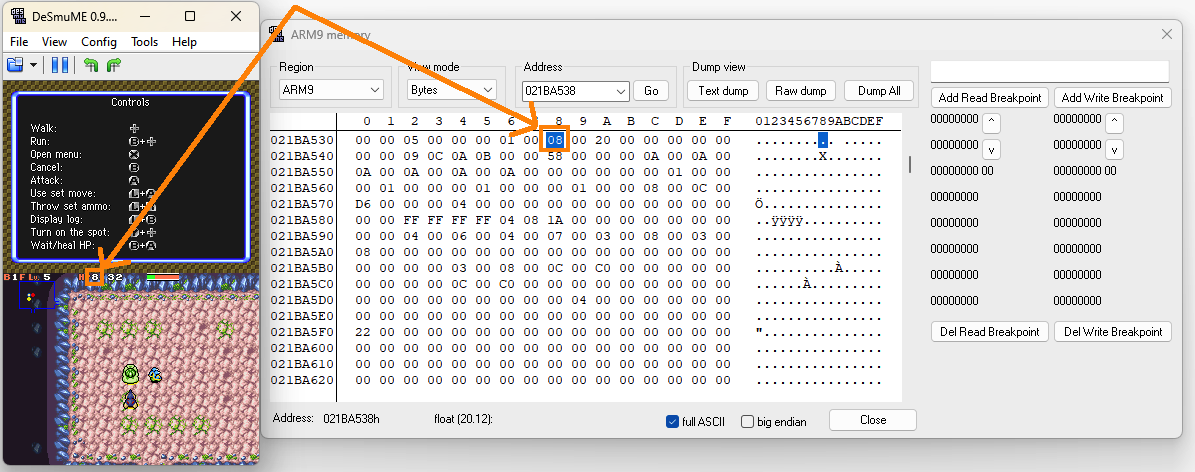

Next, jump to address 0x21BA538. This area contains more values related to the player and partner Pokémon. Change the value at 0x21BA538 to 08, and you’ll notice that the player’s health (HP) changes in-game to match the value you entered.

Editing memory values

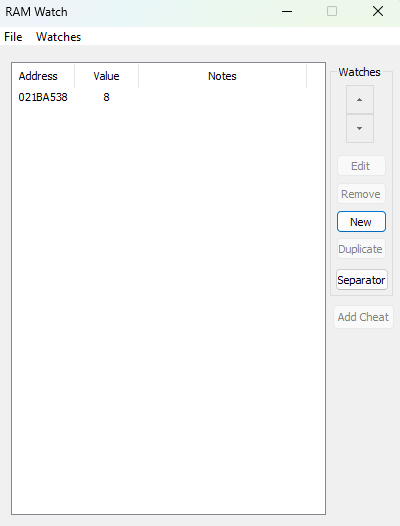

A supplement to the memory viewer is the RAM Watch, accessible at Tools > RAM Watch…. You can pin specific memory addresses in this window to keep an eye on their values.

RAM Watch window

RAM Search

The RAM Search view allows searching memory for specific values. It can be acccessed via Tools > RAM Search…, which will bring up the window below.

RAM Search window

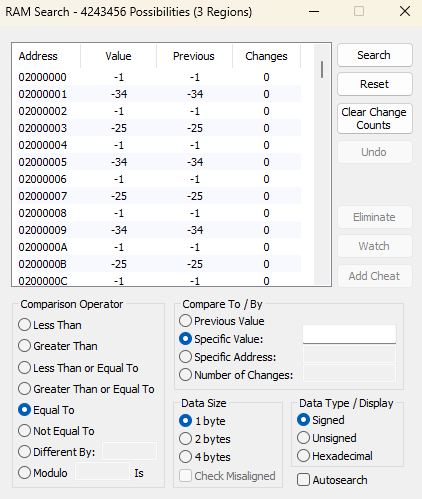

RAM Search is a valuable tool for finding the addresses of relevant in-game values. As an example, let’s search RAM to locate which address the player’s HP is stored at.

To search for a value, enter the value to search for, configure the search using the available options, and press Search. Let’s search for the player’s current HP, which we set to 8 earlier.

Searching for a value

8 is a small value, so it commonly occurs throughout memory. We could scroll through each address in the search and try each of them to see which one represents the player’s HP, but there’s a better way.

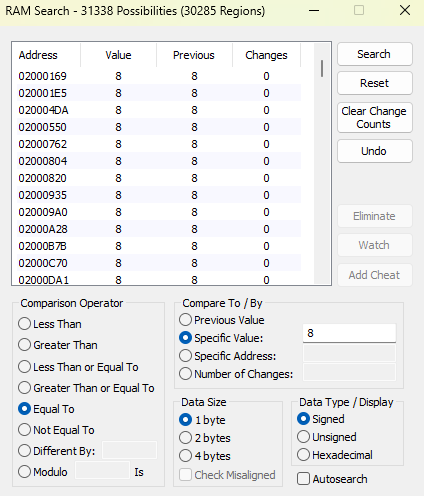

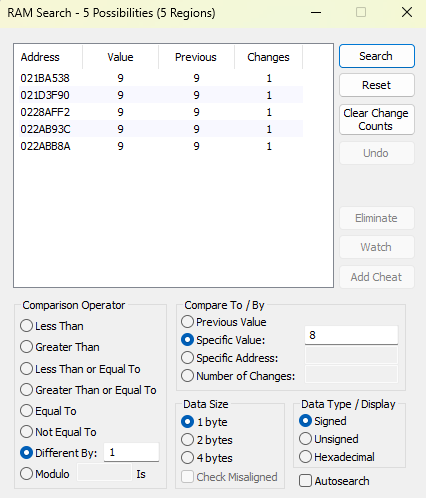

Without closing RAM Search, go back to the game and walk around for a bit until your HP regenerates to 9. Next, change the comparison operator to Different By and enter 1 next to it, and click Search again. This will limit the search to the memory addresses found in the previous search, and look for any values that have increased by 1 from before. Since the previous search was for the value 8, this will search for any values that changed from 8 to 9 between the two searches.

Searching for changed values

Now that the search is narrowed to a handful of values, you can try changing the values at each of these addresses to find which one controls the player’s HP. You’ll find that the correct address is 0x21BA538.

To set up the above example, we manually changed the player’s HP to 8, which requires knowing the address of the player’s HP ahead of time. If you didn’t already know the address, you could lower your HP through in-game means, such as finding an enemy and letting it attack you.

Disassembler

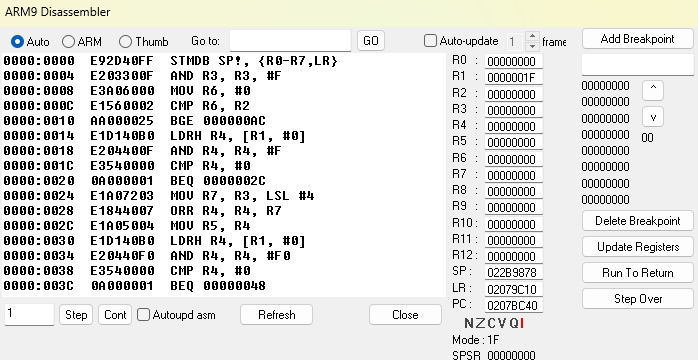

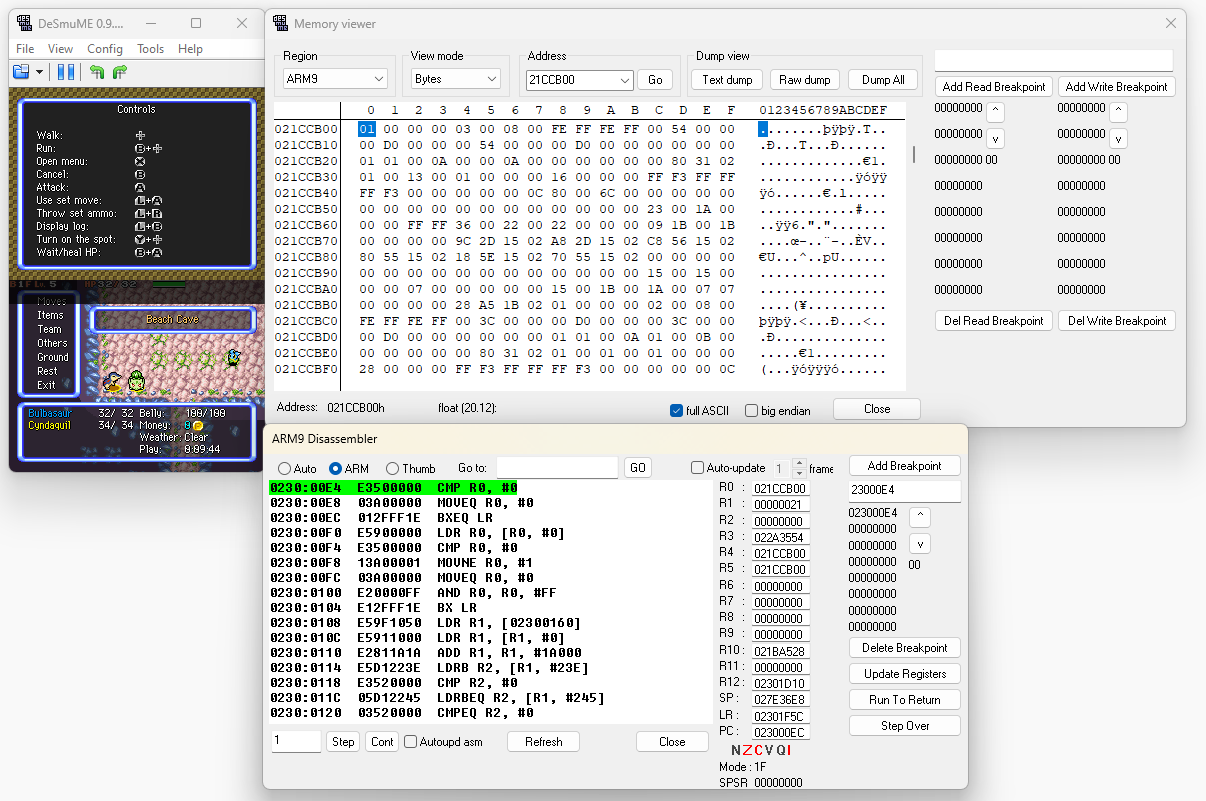

In DeSmuME, the disassembler is a tool that exposes several useful debugging features, including setting breakpoints to pause game execution, stepping through assembly code as it runs, and viewing register values. The disassembler is accessed via Tools > Disassembler, which will open both an ARM9 and an ARM7 disassembler. Since the code we’ll be looking at is for the ARM9 CPU, use the ARM9 disassembler.

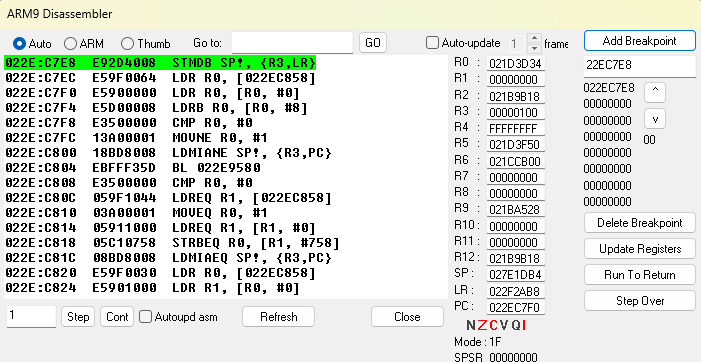

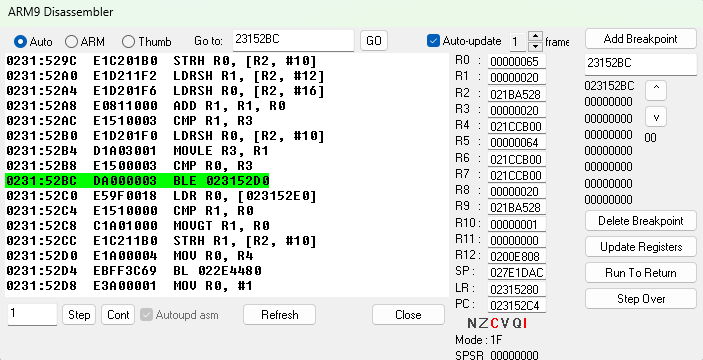

ARM9 Disassembler window

Breakpoints

Similar to debuggers in higher-level languages, a breakpoint pauses program execution if a specific line of code is reached. This has several uses, like figuring out whether a line of code is reached when performing an action in-game, or stopping program execution at a specific function to debug it.

As a demonstration, let’s set a breakpoint at the beginning of the function FUN_022ec7e8. Under the button that says Add Breakpoint, enter the value “22EC7E8”, then click Add Breakpoint. Now try to move your character around in-game. This will execute FUN_022ec7e8 and hit the breakpoint, pausing the game’s execution. The green line indicates the instruction that is about to be executed.

Hitting a breakpoint

On the left is a view of the assembly code, along with the addresses and hex data like in Ghidra. You can go to a specific instruction by entering the address into Go to: and pressing GO.

Underneath the assembly view are Step and Continue (Cont) buttons, which act like they would in a standard IDE’s debugger. Step causes the program to step forward an instruction, or multiple if you change the number next to the button. I recommend turning on Auto-update at the top of the window when stepping through code, or else you’ll need to click the Refresh button to update the view every time you step to a new instruction. Continue will continue program execution. Sometimes, the game will stay paused after pressing Continue; if this occurs, unpause the game with the pause/play button in the game window.

To the right of the assembly view are the registers and their values, which you can view and edit. When editing register values, make sure Auto-update is disabled to avoid the register value instantly reverting when you try to edit it. Press Update Registers to apply the register changes when you finish editing them.

On the right side of the window are the active breakpoints. Note that if you click Delete Breakpoint, the breakpoint at the top of the currently displayed list will be deleted. You can scroll through the list with the adjacent arrow buttons to maneuver the desired breakpoint into place for deletion.

The Run To Return and Step Over buttons work inconsistently in my experience. Use them at your own risk.

Watchpoints

A watchpoint pauses program execution if a specific address in memory is read from or written to. This is useful for finding which part of the code is used to manipulate a certain value in memory, and can also be used to track a memory value whose purpose hasn’t been figured out yet. Watchpoints are known as read breakpoints and write breakpoints in DeSmuME.

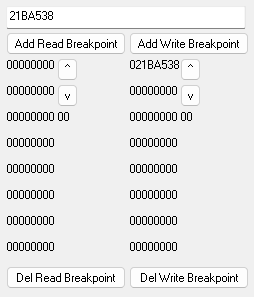

Watchpoints can be set in the memory viewer. To demonstrate watchpoints, let’s watch the player’s HP value. Open the memory viewer and look to the right to find the watchpoint editor. Enter 21BA538 into the text box, then click Add Write Breakpoint.

Adding a write breakpoint

With the write breakpoint in place, move around until your HP naturally restores. When the HP restoration occurs, the watchpoint will pause the program. Go to the disassembler and either hit Refresh or turn Auto-update on, then go to the address that is currently in the pc, which should be 0x2311264. Scroll up a bit (make sure your cursor is outside the assembly view) to find the green highlight marking the next instruction to be executed, 0x231125C. Remember that the pc can be slightly ahead of the current instruction being executed because of how the CPU works.

Disassembler view after hitting the write breakpoint on the player’s HP

Note that the instruction the game is paused on is the instruction after the instruction that accessed the watched address, meaning that the instruction that wrote to the HP value is at 0x2311258. This address contains the instruction strh r1, [r7, #10]. You can see the address 0x21BA528 in r7, and adding 10 to that (as the strh instruction does) gives you 0x21BA538, the address of the player’s HP. The value in r1 contains the new value that the player’s HP was just set to, which you can also see at address 0x21BA538 in the memory viewer.

If you look up the instruction at address 0x2311258 in Ghidra, you’ll find that the instruction is within FUN_02311088, indicating that this function handles passive HP restoration.

Save states

Save states are a standard part of most emulators, allowing the game’s state to be saved and loaded at any time. In addition to their standard gaming uses, save states can also be used at a more granular level while debugging the program.

DeSmuME has ten save state slots. To save or load a state, you can use File > Save State and File > Load State, or their respective hotkeys. If you are stepping through assembly code in the disassembler, save states can be useful for the debugging process if you want to step through code with the same game state multiple times. Note that loading a save state while stepping through code might not refresh the graphics in-game until program execution continues, but this does not affect the ability to step through the code.

DeSmuME wrap-up

We’ve seen some of the general tools in DeSmuME for inspecting and debugging the live game. The emulator has a number of more specialized tools that this tutorial won’t go into, such as viewing the currently loaded palettes, tiles, and backgrounds. You may wish to check them out on your own if those strike your fancy.

Reverse engineering strategies

With assembly knowledge, Ghidra, and DeSmuME, we have all the tools to start reverse engineering a game. The last section of this tutorial will discuss reverse engineering strategies to find where functionality lives in the ROM and in memory.

The DeSmuME section of this tutorial discusses a couple of strategies using RAM Search and watchpoints, so check those out if you haven’t already.

Following a value backwards through assembly

One way to find the location of a specific value is to trace related values backwards through the assembly to find where they came from. This might lead to the value you are looking for.

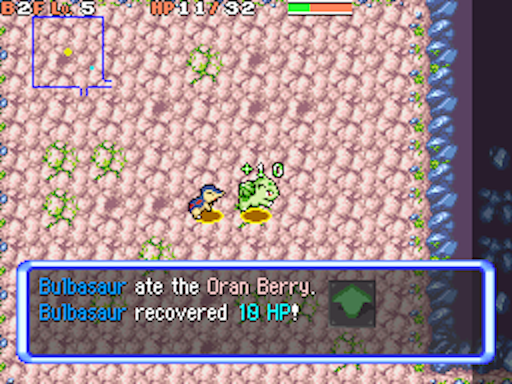

To demonstrate, let’s find the place in code that determines how many hitpoints (HP) a certain healing item will heal your character. In-game, explore the dungeon until you find a blue berry on the floor, called an Oran Berry. You might not find one on the floor you’re on; if you’ve explored the floor and found nothing, look for a staircase to proceed to the next floor and continue the search.

An Oran Berry on the ground to the right of the player

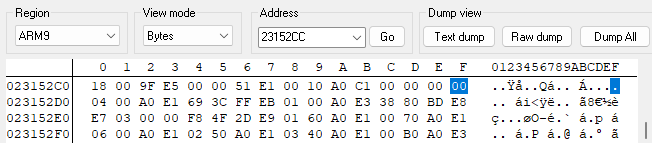

Once you find an Oran Berry, walk over it to pick it up. The berry heals 100 HP (up to your max HP), and our goal in this demonstration is to change the berry to heal only 10 HP. This requires knowing where the value 100 is stored within the game’s code.

You’ll need to have low HP to observe how much the berry heals, so go to the memory viewer and set your HP (address 0x21BA538) to 01. Press X to open the menu, and go to Items to see the Oran Berry in your inventory. Make a save state so you can come back to this point, as you’ll be repeatedly eating the berry to debug what happens in code when you eat it. Once you’ve made a save state, select the berry, choose to eat it, then choose the player character, which will heal all of the player’s HP.

Normal Oran Berry behavior, healing up to 100 HP (capped at the player’s max HP)

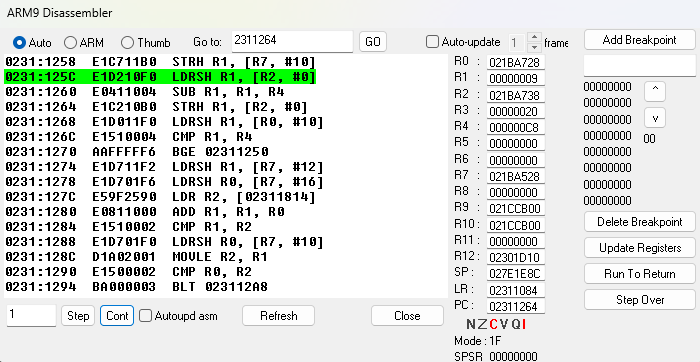

Now that we’ve seen what the Oran Berry does normally, reload the save state and use the memory viewer to add a write breakpoint at address 0x21BA538 (the player’s HP). Eat the berry again, which will hit the write breakpoint and pause the game. Go to the disassembler, go to the value in the pc, and scroll up a bit to find the instruction the game is paused on. The instruction directly before that is what we are looking for, the strh r0, [r2, #10] at address 0x231529C.

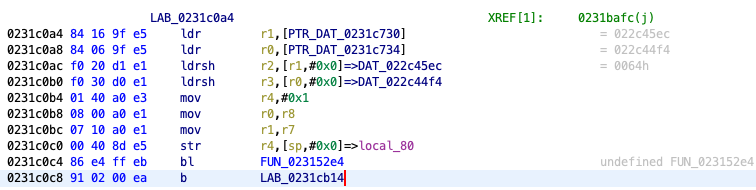

Hitting the player HP write breakpoint after eating a berry

r0 was just stored into the player’s HP, so look at the value of r0 in the disassembler to find that it currently has the value 0x65 (101 in decimal). This lines up with the Oran Berry’s 100 HP of healing plus the player’s 1 HP. There is code later to cap the player’s HP at their max HP, but the uncapped HP is workable as is.

The two previous lines of assembly are also of note.

ldrsh r0, [r2, #10]

add r0, r0, r5

The game loaded the player’s HP ([r2, #10], the same as the strh instruction), then added the value of r5 to it. r5 has the value 0x64 (100), which matches the Oran Berry’s healing amount of 0x64 (100).

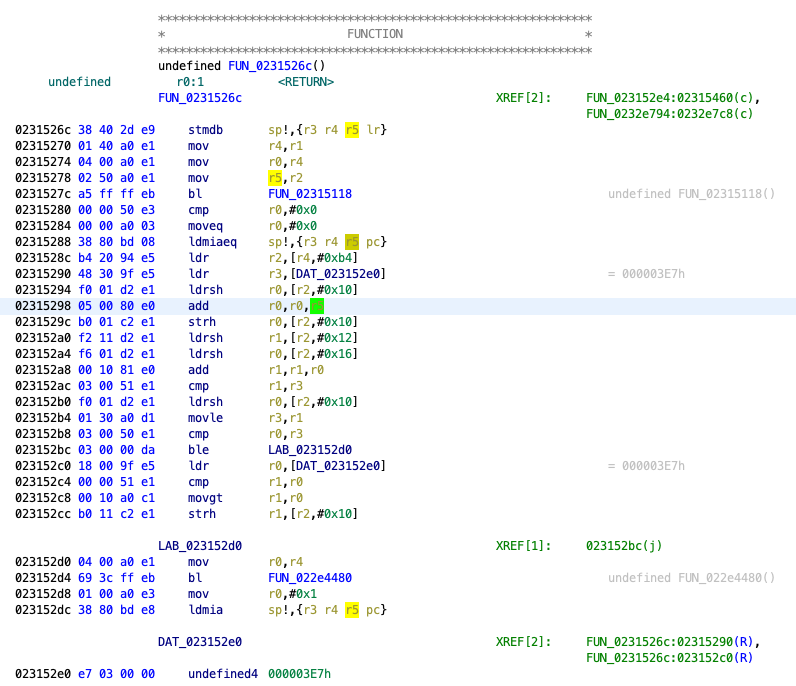

Now let’s look for where the value 0x64 was assigned to r5. Go to the address 0x231529C in Ghidra to find the same instructions that are in the disassembler. Middle-click r5 in the add r0,r0,r5 instruction to highlight its usages, then scroll up in the function. There is another reference to r5 at 0x2315288 with ldmiaeq sp!,{r3 r4 r5 pc}, but this is an early return from the function (indicated by popping from the stack onto the pc), so we can ignore it. Near the top of the function is what we are looking for, address 0x2315278 with mov r5,r2.

Tracing the healing amount of the Oran Berry to the top of the function

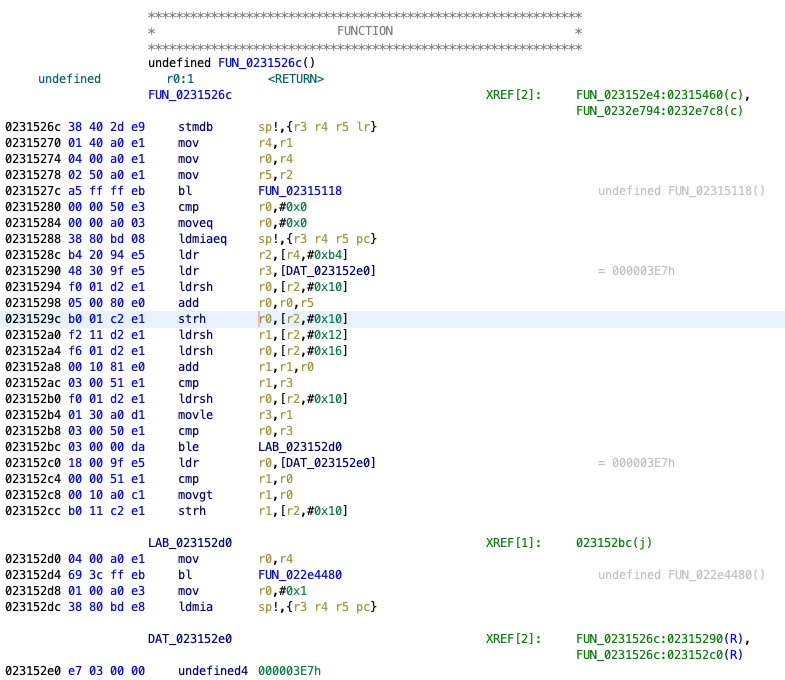

The 0x64 in r5 came from r2, but there are no more references to r2 between here and the start of the function. Remember that registers r0-r3 are designated for passing arguments into a function. This means that r2 is the third parameter of FUN_0231526c, and the 0x64 came from the code that called FUN_0231526c. The next step is to find the caller of this function.

Scroll to the bottom of FUN_0231526c, and you’ll find the ldmia instruction at 0x23152DC marking the end of the function. Make a breakpoint in DeSmuME at 0x23152DC, then continue program execution to hit the breakpoint. Note that before hitting the breakpoint, you’ll hit the write breakpoint for player HP again; this is where the player’s HP is capped at their max HP.

Once you hit the breakpoint at the end of the function, step ahead one more instruction to see the program return from the function. Go to the new value of the pc and scroll up a bit to find the current instruction.

Outside the functionFUN_0231526c

Above the current instruction, you can see the bl 0231526c at address 0x2315460, confirming that this is the place that calls FUN_0231526c. Go to address 0x2315460 in Ghidra.

The call toFUN_0231526cat address 0x2315460 in Ghidra

We were looking for where r2 was assigned to 0x64, so look at the lines prior to the function call. We can see a mov r2,r5 at address 0x231545C immediately prior to the function call, meaning that the 0x64 came from r5. Middle-click r5 and look for instructions that write to it.

At 0x2315378 is the instruction add r5,r5,r0, asr #0x8, which writes to r5. Let’s see if this instruction is reached when eating an Oran Berry. First, delete the existing breakpoints and watchpoints, since we no longer need them. Put a breakpoint at 0x2315378, reload your save state, and eat the berry. The breakpoint will not be reached at any point when eating the berry, which means this line of code is not relevant to us. Continue looking through the function for other places where r5 could have been assigned.

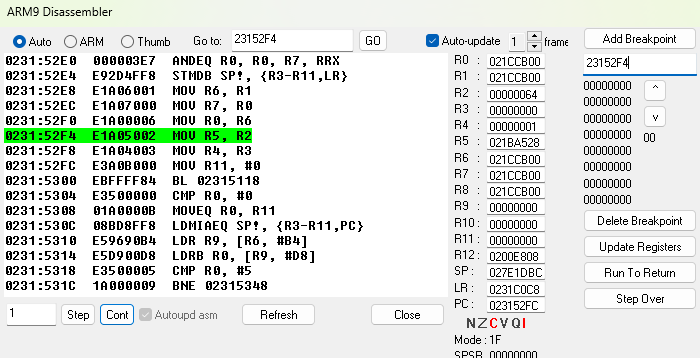

The next instruction of interest is near the start of the function, a mov r5,r2 at address 0x23152F4. r2 is not assigned between here and the start of the function, so it is once again an argument passed into the function. We’ll need to trace the value to the place that called FUN_023152e4, and follow r2 from there to see where it gets assigned to 0x64.

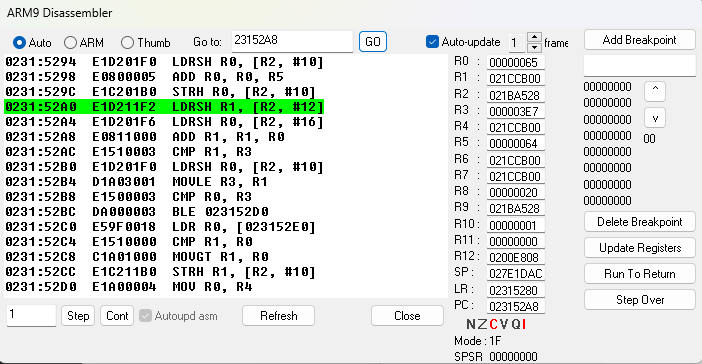

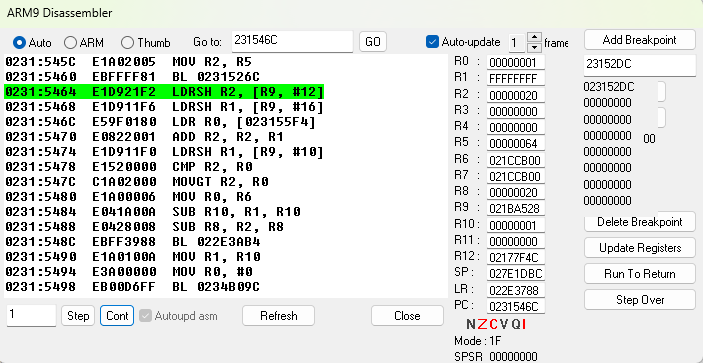

This time, let’s use a different way of finding the calling function. Delete the previous breakpoint, add a breakpoint at 0x23152F4, then reload your save and eat the berry again. The breakpoint will be reached this time, so head to address 0x23152F4 in the disassembler.

Breakpoint at address 0x23152F4

Since this is the start of the function and no other functions have been called yet, the value of register lr contains the return address to the calling function, address 0x231C0C8. Go to address 0x231C0C8 in Ghidra.

Ghidra at address 0x231C0C8

We can see the function call for FUN_023152e4 at 0x231C0C4. Back to finding where r2 was assigned to 0x64, there is a reference to r2 a few lines up. Look at lines 0x231C0A4 and 0x231C0AC.

ldr r1,[PTR_DAT_0231c730]

...

ldrsh r2,[r1,#0x0]

This loads an address into r1 from data value PTR_DAT_0231c730, then loads the value at the address into r2. To the right of these instructions, Ghidra’s analysis has found that PTR_DAT_0231c730 points to the address 0x22C45EC.

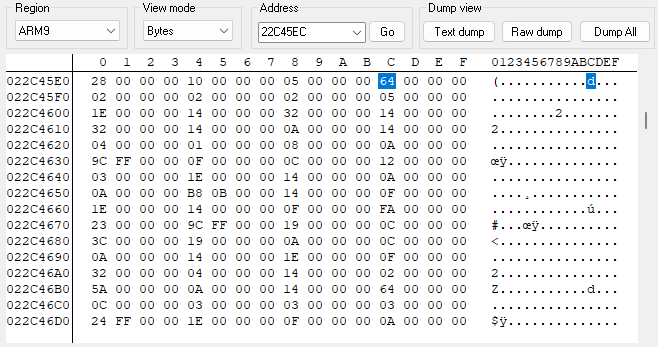

With this address in mind, go back to DeSmuME and go to address 0x22C45EC in the memory viewer. You will find the value 0x64 at the address, confirming that this is the location of the Oran Berry’s HP heal amount.

The location of the Oran Berry’s heal amount

To test the address we found for the heal amount, reload your save state, change the 0x64 at address 0x22C45EC to 0x0A in the memory viewer (0x0A = 10 in decimal), and eat the Oran Berry again to see how much it heals. Delete the breakpoint from earlier to avoid hitting it now that we’re done with it.

The changed Oran Berry heal amount

Success! We’ve found that the Oran Berry’s heal amount is stored at 0x22C45EC.

Which overlay is the Oran Berry’s heal amount located in? As a reminder, the overlays we loaded are at the following addresses in memory:

- Overlay 10: 0x22BCA80

- Overlay 29: 0x22DC240

- Overlay 31: 0x2382820

Looking at the three addresses, overlays 29 and 31 are past the address 0x22BCA80, which leaves overlay 10 as the overlay where this value is. By subtracting the value’s address from the overlay’s address, you can figure out the offset of the value within the overlay file (as opposed to in memory). 0x22C45EC - 0x22BCA80 = 0x7B6C. You can verify this by opening overlay_0010.bin in a hex editor and going to byte 0x7B6C.

Technically, if you changed the value at offset 0x7B6C in overlay_0010.bin, then repackaged the ROM files back into a single .nds file (using the same tools use to unpack it), you’d create a minimal ROM hack that nerfs the Oran Berry’s healing. Creating ROM hacks is out of the scope of this tutorial, but this demonstrates a piece of the process for creating these types of hacks.

Reading assembly forwards

Perhaps obviously, reading assembly forward is a way to figure out how game logic works.

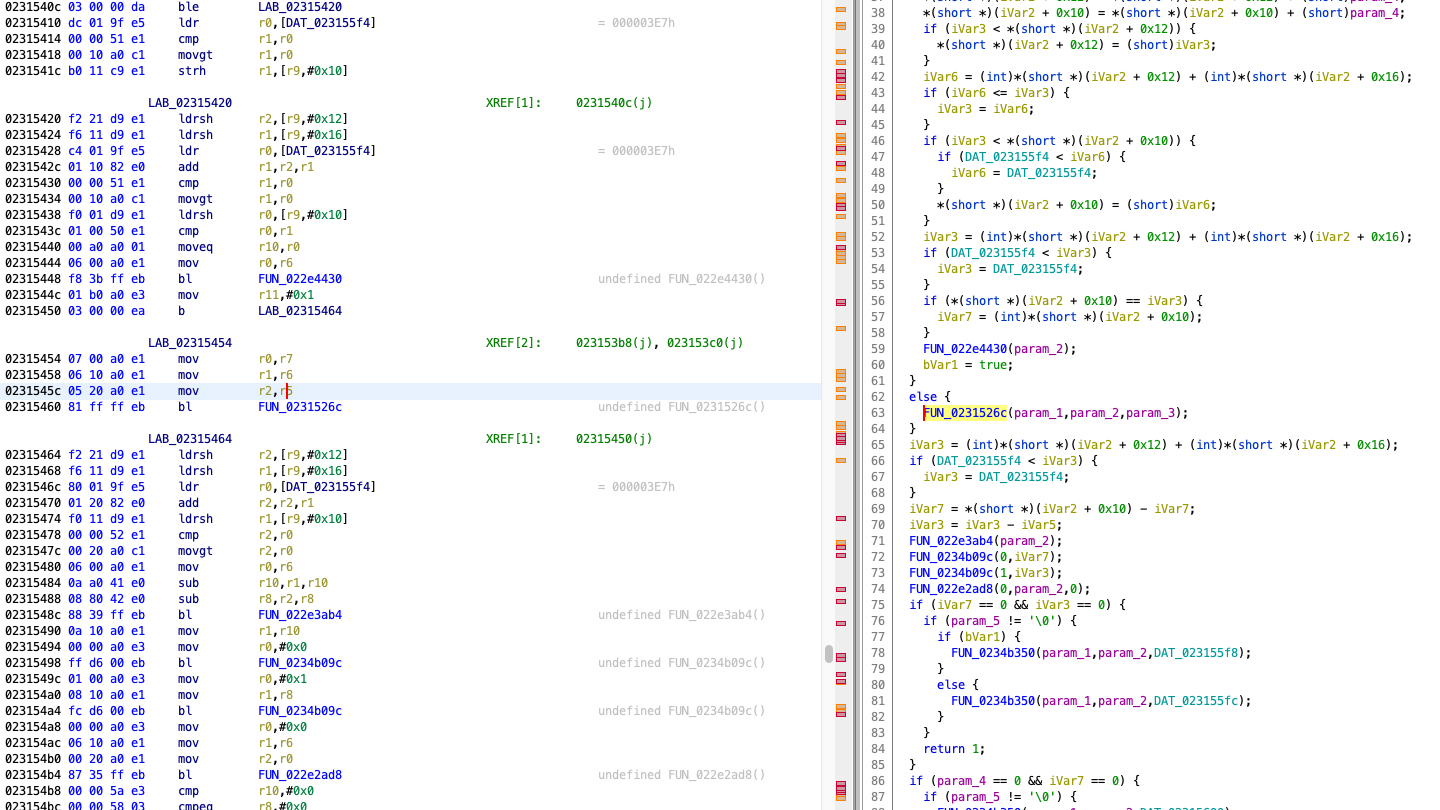

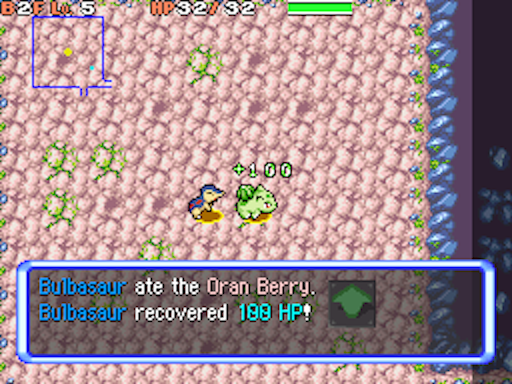

Let’s explore the same functionality from the previous section (where the player’s HP is healed from a berry) and look for the code that caps the player’s HP at their max HP. Go back to address 0x231529C in Ghidra.

Assembly code for healing the player with a berry

We saw that the instruction at 0x231529C, strh r0,[r2,#0x10], sets the player’s HP to the heal amount + the player’s current HP. At address 0x23152BC, you can see a conditional ble statement that checks if r0 is less than r3. Alternatively, you can look at the decompilation to find this same conditional. If the conditional is not met, then another value is stored in the player’s HP (the strh r1,[r2,#0x10] at 0x23152CC).

Since the player’s HP is accessed using an offset, this is an indicator that the player’s HP is within a struct, likely containing other values related to the player. The player’s HP is at offset 0x10 in this struct.

Although we could trace the values of r0 and r3 in the assembly, it might be easier to set a breakpoint at this spot and see what the values are when the game is running. Add a breakpoint at the ble instruction, 0x23152BC, then reload the save state and eat the Oran Berry.

Hitting the breakpoint at 0x23152BC.

r0 is 0x65, the calculated sum of the Oran Berry’s healing amount and the player’s HP (100 + 1 = 101 = 0x65). r3 is equal to the player’s max HP, which is 0x20 = 32 in the screenshot above, but it may be a slightly different value for you depending on which Pokémon you’re playing as. This means the code checks if the calculated heal amount is greater than the max HP, and caps the player’s HP at its max HP if so. If you step through the next few instructions, you’ll see the value in r1 (also equal to the player’s max HP) assigned to the player’s HP.

For further confirmation, we can change the strh instruction at 0x23152CC so that it doesn’t cap the player’s HP. In the disassembler, you can see that this instruction’s hex value is E1C211B0. Go to address 0x23152CC in the memory viewer, and you’ll find the value B011C2E1 there, which is little endian for E1C211B0. Reload your save state, then change these four bytes to 00, which will change the instruction to a no-op (an instruction that does nothing).